I’M NOT ENTIRELY CERTAIN if Charles Dickens ever rode the London Underground . . . but, in theory, he could have – and that’s good enough for me.

This thought first occurred to me back in early August. I was in London, and I’d just left the Charles Dickens Museum at 48 Doughty Street. The museum was interesting, but my most persistent fascination throughout the whole of that trip was not any single sight that London had to offer. More than Big Ben or the British Museum, it was the great subterranean network beneath them that most captivated me. The Tube was always on my mind. So many stations, so many lines . . . so many monstrous escalators.

The spectacle of it got me thinking. Where did a subway system this extensive and this renowned fit into the global public transit timeline? That it’s the first system of its kind is not surprising, but I never would have guessed that its oldest line opened on January 10, 1863[i] – more than seven years before Dickens’ death.

I don’t know why this bit of information left such an impression on me. It’s sort of like learning that Mary Pickford died after the release of Apple’s first home computers. Silent movies and personal computing shouldn’t overlap. Neither should Victorian novelists and subway stations. And yet overlap they do.

In 1863, Toronto was just twenty-nine years past incorporation, and still ninety-one years away from having a subway of its own. Visiting London, and coming to appreciate the long history of its Underground, I grew curious about our metro systems – not just Toronto’s, but the others across Canada, too. Where were those other metros? And, while we’re at it, what exactly is a metro?

This last question caused me a surprising amount of trouble. The terminology used to describe urban rail transit is extensive and overlapping: the subway, the metro, the light metro, the light rail. While there isn’t much consensus when it comes to precisely categorizing public transit systems, “metros” are probably best defined as rapid transit systems with total grade separation, typically serving large metropolitan areas.

Taking this as our definition, Canada has four such systems: the Toronto subway, the Montreal Metro, Vancouver’s SkyTrain, and the new REM in Greater Montreal. We’re going to focus on the first three in this piece.

These three systems differ from one another in fascinating and pretty fundamental ways, and the reasons for these differences are as varied as the systems themselves.

Let’s take a look at how the lessons of the past, the world expos of the future, and the unbearable traffic congestion of the present created the metro systems of Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver.

Toronto

LIVING IN TORONTO, it’s easy to complain about the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) – because, like traffic and construction (two things which are influenced by the TTC and which influence it in turn), it feels like one of the inevitabilities of life in this city. We’d do well to remind ourselves that the TTC is far from inevitable. History shows us that it emerged as the conscious solution to decades of transit anarchy, and that it first appeared because Torontonians pretty much demanded it.

As was the case in many North American cities, public transit in Toronto first appeared in the form of privately run systems of buses and streetcars, whose shortcomings were eventually supplemented by city-run initiatives. From 1849 until the end of the First World War, Toronto transit companies came and went, often maintaining variable standards of quality control and inconsistent passenger fares. By the end of the war, “there were nine separate systems collecting nine separate fares, [and a] journey by transit within the city limits cost anywhere from two . . . to fifteen cents.”[ii] Unsurprisingly, Torontonians were growing increasingly fed up with this state of affairs, and they voted for a full municipal takeover of the various transit systems in 1920. The Toronto Transportation Commission (later to be drastically renamed the Toronto Transit Commission) took control of the city’s various lines on September 1, 1921.[iii]

The decades which followed would see the TTC make various improvements to the city’s transit services. Deteriorating streetcar tracks were repaired and replaced; this initiative included extensive work on what was then considered “one of the most complicated [track] intersections on the continent”: the King-Queen-Roncesvalles junction.[iv] New, modern streetcars were introduced over the decades: the Peter Witt streetcar in 1921, the Presidents’ Conference Committee (PCC) car in 1938[v] and, in 1979, the recently retired CLRV.[vi]

(Side note: You can still ride these old streetcar models at the Halton County Radial Railway Museum (HCRR) in Milton (Figure 2). Founded by a group of transit enthusiasts in 1954 (a crucial year in our story, as we’re about to see), the HCRR is home to a number of historic rail transit vehicles. In addition to the streetcar models mentioned above, the museum hosts two of the first cars ordered for the launch of the Yonge subway in – yes – 1954.)

Talk of a Toronto subway first began a decade before the TTC existed. In the city’s 1910 mayoral race, Horatio Hocken made the subway his key campaign issue and promise, and he had a slogan to match: “Tubes for the People.” Although Hocken lost the election, city council commissioned a subway design proposal the following year.[vii] This first proposal had the subway running from Bay and Front to Yonge and St Clair.

Nothing ultimately came of this proposal – and the prospect of a Toronto subway grew more remote when the First World War came along and kicked off what might be the most globally disruptive period in history this side of the Black Death. While the topic of the subway cropped up again from time to time[viii] it remained a largely speculative discussion through the War-Depression-War years. As previously mentioned, the TTC had plenty of other work to do on the city’s streetcar tracks and fleet. The introduction of modern buses (gas-powered, with rear-mounted engines, and greater commuter capacity than their van-like predecessors) was another major initiative during this period.[ix]

It was only towards the end of the Second World War that the TTC once again began to think seriously about the development of a subway system. Toronto historian Mike Filey writes:

“. . . even as Torontonians continued to pray for an end to the war . . . TTC officials were already working on plans to construct the nation’s first subway system, having created the Rapid Transit Department . . . on January 1, 1944.”[x]

What had prompted Toronto to finally move forward on the subway? Was it radical social change brought on by international conflicts and economic depression? Not exactly. Simply put, traffic congestion had finally got to be too much. The following is a statement from the TTC in 1945:

“The present congestion of traffic on Toronto streets threatens the very economic life of our city . . . The Commission does not propose to stand idly by and allow this deterioration of its services and of the city itself to take place. There must be a gradual separation of public and private vehicles, both of which are now trying to operate on the narrow streets originally designed for horse-drawn traffic.”[xi]

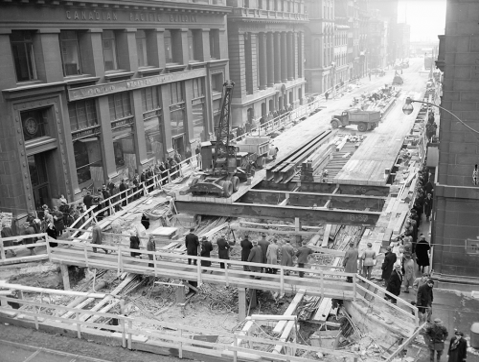

It would be another few years before Toronto, recovered from postwar shortages and ready to ring in the ’50s, began subway construction on September 8, 1949.[xii] The subway’s location was a natural choice: it would be built beneath one of the most congested of Toronto’s many congested roadways: Yonge Street (Figure 1).

Embarking on this project, Toronto opted for the cut-and-cover method – the same method that was used nearly a century earlier when work on the London Underground began in 1860.[xiii] Cut-and-cover involved digging up much of Yonge Street, and led to a sight which has become familiar to Torontonians: that of extensive construction in major commercial and vehicular arteries. That’s not to say that every effort wasn’t made to keep roadway disruptiveness to a minimum. The construction process was as follows: piles were driven in along either side of the excavation area (in this case, Yonge Street); then, workers ‘cut’ into the street, digging out the area and removing/rerouting utility lines as they went; after that, steel beams and timbers were used to ‘cover’ the excavation area, thereby allowing road-level traffic to continue while work carried on underground.[xiv]

Street closures and detours – advertised by the Toronto Star – give one a sense of the construction’s progress. June 16, 1952: Bloor Street is closed between Yonge and Church.[xv] June 21 of the same year: Dundas Street traffic is to be diverted between Bay and Victoria.[xvi][1] July 28, 1953: subway construction necessitates a diversion on St. Clair between Yonge and Alvin.[xvii]

Members of the public were invited to participate in the project that would become such a fixture in their lives over the four-and-a-half years that the subway was under construction. The bystanders who, day after day, lined Yonge Street to watch the work’s progress, were termed “sidewalk supervisors” (Figure 3). The TTC supplied the curious with informational brochures.[xviii]

Work progressed quickly. The first new subway cars (purchased from the Gloucester Railway Wagon and Carriage Company in England) arrived in Toronto on July 30, 1953, and were put on display at the CNE later that summer.[xix] That December, the Toronto Star reported that transit tickets were to be phased out in favour of tokens, ten million of which had already been ordered “from a Montreal firm.”[xx]

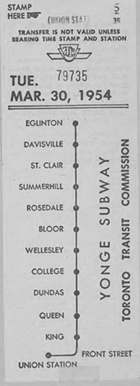

Running from Union Station to Eglinton Avenue, the Yonge Street subway launched on March 30, 1954.[xxi] Opening ceremonies were held at Davisville Station.[xxii] The first train departed for Eglinton Station (the new line’s northernmost point) at 11:50am, before travelling southbound to reach Union at ten minutes past noon. Service on the Yonge streetcar line came to an end that same day.[xxiii]

The next three decades saw various extensions to the system. The University line, originally running from Union to St. George, opened on February 28, 1963.[xxiv] The east-to-west Bloor-Danforth line (from Woodbine to Keele) followed on February 26, 1966;[xxv] extensions eastward to Warden and westward to Islington opened on May 11, 1968.[xxvi] A decade later, the University line was extended north to Wilson.[xxvii] The Kipling and Kennedy extensions to the Bloor-Danforth line (1980), the Scarborough RT (1985), the Sheppard Line (2002), and further extensions to the Yonge-University line have followed.[xxviii]

In spite of these later developments, many in Toronto will point out that the past several decades have seen relatively little progress when compared to the first quarter-century of subway construction. It seems as though, with every new Toronto mayor and every change of Ontario premier, transit plans are developed, modified, scrapped and replaced. But the politics of Toronto transit is a subject too vast to be given any justice here – and besides, this piece is all about the good times: the victory of getting the Yonge line open, and the unqualified praise that was sung for it from far and wide . . . right?

Montreal

WALTER O’HEARN’S COLUMN in the March 31, 1954 issue of the Montreal Star, entitled “Toronto Subway System Gem-Like Production” conveys what this reader would describe as mixed feelings: “To hundreds of thousands of Torontonians it was the greatest show on earth. I wouldn’t go quite that far,” O’Hearn writes. He praises the subway cars for their comfort and assures his readers that riders are in for a smooth journey, “[once the TTC’s] motormen learn a little more about their air brakes.” Toronto’s single north-south line is “a glorified shuttle really.” My absolute favourite of O’Hearn’s observations is that, while he has never seen the Moscow subway, he’s been assured that its stations are adorned with gorgeous murals. By comparison, “the first Canadian subway doesn’t try to compete. Instead the planners have gone in for soft pastels – ivory with black trimmings – grey and red, pale green. A little like modern bathroom designs out of Home and Garden. But fresh and pleasant.”[xxix]

While I wouldn’t go so far as to suggest that Montreal was jealous of the Yonge subway, I think its launch did encourage a healthy spirit of one-upmanship. Montreal would take notes on the Toronto subway, and would ensure that its own metro, once launched, would improve on what had come before it.

For much of this country’s history, Montreal has been its largest city. According to census data, Toronto’s population surpassed Montreal’s only after the former’s 1998 amalgamation. (In 1996, the last census year prior to amalgamation, Toronto ranked as the country’s third largest municipality, behind Montreal in first place and Calgary in second.[xxx])

The 1951 census (the last before the opening of the Yonge subway) put Toronto’s head count at 675,754 to Montreal’s 1,021,520. In other words, Toronto’s population was just about two thirds of Montreal’s.[xxxi] This fact was not lost on either city when work on the Yonge subway began. From a 1950 article in the Toronto Star: “Montrealers still cannot figure out why Toronto can have a subway under construction while their own somewhat larger city must for some time do without one.”[xxxii]

Visiting Toronto in June 1955, then-mayor of Montreal Jean Drapeau toured the year-old subway system in the company of his local counterpart, Nathan Philips. As reported in The Montreal Star, Drapeau informed Philips that the Toronto subway was not, as so many seemed to believe, the first in Canada. That honour went to Montreal:

“‘It’s quite true,’ Mayor Drapeau [said]. ‘About 40 years ago the CNR built a four-mile subway under the mountain. Most Montrealers don’t know about it.’”[xxxiii]

It appears Drapeau was referring to the Mont Royal Tunnel, built by the Canadian Northern Railway between 1912 and 1918 to serve as a rail corridor to the port and downtown Montreal.[xxxiv] Calling this tunnel a subway – in the sense that Toronto’s subway was a subway – was a bit of a stretch.

Drapeau estimated that it would be at least two years before Montreal had a “Toronto-style subway.” Two years later, Drapeau would be voted out of office – but he would return in 1960, and would go on to be Montreal’s longest serving mayor. Getting Montreal’s metro going would take longer than Drapeau had first anticipated – but the final result would be worth the wait.

Despite Drapeau’s tongue-in-cheek truth-stretching on the topic of the Mont Royal tunnel, Montreal had, in fact, first begun floating the idea of a subway system in 1910, right around the time that, over in Toronto, Horatio Hocken was running his “Tubes for the People” campaign. In Montreal, these early proposals envisioned the subway as a series of streetcar tunnels, designed to separate trams from other road traffic, thereby easing congestion.[xxxv]

As was the case in Toronto, Montreal’s transit system in the early 20th century was in large part privately operated. Montreal’s main operator (the Montreal Tramways Company), went into decline over the decades, until the Montreal Transportation Commission (an ancestor of today’s Société de transport de Montréal) took control of the streetcar system in 1951.[xxxvi]

Work on the Montreal Metro would begin a decade later, after Jean Drapeau entered his second term as mayor in 1960.

From the very beginning, the Montreal Metro set out to be a self-consciously spectacular project. In The Lost Subways of North America, Jake Berman writes:

“The Montreal Metro wasn’t built to solve a transport problem . . . Jean Drapeau . . . wanted a mega project to show off Montreal to the world, and the metro was it.”[xxxvii]

The timing was right, and tight: the metro had to be ready in time for the upcoming 1967 International and Universal Exposition – better known as Expo 67.

Showing Montreal off to the world required that the city build a metro system which was absolutely unique. Architect Guy R. Legault made a number of proposals which influenced both the metro’s construction methods and its overall character: building stations parallel to (rather than on) main streets, so as not to disrupt businesses and foot traffic on the city’s main arteries; developing wide walkways within stations, the better to integrate with Montreal’s “Underground Village” (on which construction began in 1962); and working with a different architect on every metro stop, resulting in stations of unique design, each different from the others.[xxxviii]

Construction of the metro began on May 23, 1962. In his remarks on that inauguration day, Drapeau declared that there was no better way to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of talking about the Montreal Metro than by actually beginning to build it.[xxxix]

Among the several features which set the Montreal Metro apart, the system was the first in North America to run on rubber tires.[xl] Drapeau and Lucien Saulnier (president of the executive committee of Montreal) had visited Paris in 1960, and had stumbled upon what was, at that time, the only metro line in the world which used this technology. The idea had been proposed – perhaps unsurprisingly – by Michelin, and had been adopted, with success, on Line 11 of the Paris Metro. Paris would continue to implement the new technology on a number of its subway lines in the decades which followed – though this project eventually stopped when steel-rail metro technology grew more efficient.[xli]

Montreal would go all in on the rubber tire metro, implementing it across the entire length of the system.[xlii] This choice necessitated that the metro run entirely underground (making it the only true one-hundred-percent subway in Canada). The reason? Montreal winters and rubber tires don’t mix.[xliii]

The design of the Montreal Metro was carefully considered – but it wasn’t without its happy coincidences. The system’s distinct subway car design – blue with a white streak running down its length – was not chosen with thoughts of Québec’s colours in mind, but rather because blue cars were thought easier to clean than Drapeau’s preferred design: white with a red line, to match Montreal’s flag and coat of arms.[xliv]

The goal had always been to launch the Montreal Metro before Expo 67 – but there was another deadline to be considered. The city had a municipal election scheduled for October 23,1966. In consideration of the latter, Drapeau set the date of the grand opening for October 14. Six of the original twenty-six stations were not ready for the launch – but at the remaining twenty, opening ceremonies were run simultaneously. The main ceremony was held at Berri-Demontigny (now Berri-UQAM) station. On cue, trains at the nineteen other stations launched towards what is still, to this day, the Montreal Metro’s central hub.[xlv]

On October 23, Drapeau was re-elected by an overwhelming majority.[xlvi]

There was at least one minor hiccup in the following months. Anyone who has ever used the metro – especially, and somewhat paradoxically, in the winter – knows that it can get a bit warm down there. The closed and completely underground nature of the system accounts for this heat, which was such that, in the summer of 1967, one metro operator fainted, causing a train to crash into a wall at the end of the yellow line. A ventilation system was quickly introduced to the stations, tunnels and cars – but, to this day, the metro can still get pretty toasty in the winter, when some of the system’s vents are closed.[xlvii]

With its efficiency of operation and beauty of design, the Montreal Metro is one of the city’s great successes, and it’s pretty much unquestionably the supreme achievement of Jean Drapeau’s nearly thirty-year tenure as mayor. The project was completed under budget and on-time.[xlviii] From the date construction began to the October 1966 grand opening, the metro took four years, four months, and three weeks to launch. In a period that was two months less than the Toronto subway’s initial phase of construction, Montreal opened twenty stations over two subway lines (with six more stops – and a third line – to come by the spring of 1967) to Toronto’s twelve on one line.

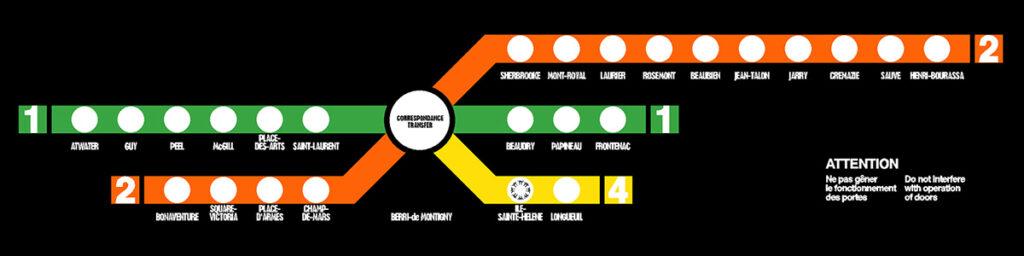

The initial network:

“. . . had three lines with 26 stations: the green line, from Atwater to Frontenac; the orange line, from Henri-Bourassa to Bonaventure; and the yellow line, from Berri-De Montigny (Berri-UQAM today) to Longueuil.”[xlix]

You’ll notice that the subway map in Figure 6designates the green, orange, and yellow lines as lines 1, 2 and 4, respectively. Drapeau’s original proposal included a line 3 which, had it been built, would have run north-south, passing through the Mont Royal tunnel. This line was never constructed, as the existing rail infrastructure (operated by CN) could not accommodate the rubber tire metro cars without significant adaptation.[l]

Extensions to the green line were opened in 1976 (to Honoré-Beaugrand) and 1978 (to Angrignon). A series of extensions to the orange line followed in the early- to mid-1980s. The blue line was developed between 1986 and 1988, and the orange line saw further extensions into Laval in 2007.[li]

Vancouver

WHEN, IN MID-1980, Vancouver was awarded the 1986 world’s fair, it became clear that the city would need to up its transit game – not only because the expo would bring global attention to the city, but also because of the expo’s theme. Expo 86 was called, in full, the “1986 World Exposition on Transportation and Communication.”[lii]

Finding itself in a situation similar to (though, because of the expo’s theme, slightly more desperate than) Montreal’s two decades earlier, Vancouver, too, needed a rapid transit system not just functional, but innovative. Whatever Vancouver developed needed to be unlike anything that had been done before.

On May 7, 1980, The Vancouver Sun ran an article entitled “Is Vancouver Ready for Snafu 86?” by John Kirkwood. Kirkwood did not hide his feelings about Vancouver’s (un)readiness to host the coming expo:

“Actually it makes a lot of sense to stage an international fair about transportation in our little old timber town in the West Coast rainforest. It would, after all, be too obvious to hold it in cities like Montreal, Toronto, or Edmonton, all of which have efficient transportation systems . . . Vancouver is a transportation nightmare and no doubt still will be in 1986 . . . So it is most fitting that the Mister Bigs of the transportation world should put on their world’s fair here in the backwoods of progress.”[liii]

“Backwoods of progress” is perhaps a bit harsh. That said, it’s worth looking into why Kirkwood might have felt the way that he did. To understand this dissatisfaction with Vancouver’s transportation infrastructure is to understand the unique solution that the city ultimately (and, spoiler alert, successfully) adopted.

By 1980, public transportation in the city went back nearly a century. The Vancouver Street Railway Company was granted authorization to build a city streetcar system in 1888, and the first stretch of electric tram line went into operation on June 28, 1890.[liv]

By 1897, the various electricity and transit providers in Vancouver, Victoria and New Westminster had, after several smaller mergers, been brought together under the name of The British Columbia Electric Railway Company Limited.[lv] The BCER was still operating Vancouver’s transit when it came under provincial control in 1961, becoming a branch of BC Hydro. By that time, Vancouver’s streetcar system, which had begun to close in the years following World War II, was shut down completely.[lvi] The next quarter century saw buses as the main mode of transportation in the city.[lvii] Following the foundation of the Urban Transit Authority (a province-run Crown corporation) in 1979, Vancouver and Victoria’s transit systems came under the control of the new organization, which was renamed BC Transit in 1982.[lviii]

Post-streetcar, people floated various ideas for the alleviation of traffic congestion and improvement of commuter experience in Vancouver. While proposals for freeway development were discussed, nothing came of them. As Berman writes:

“Vancouver started its freeway planning relatively late, and the drawbacks of freeways had become apparent by the late 1960s and early 1970s. Freeway opponents in Vancouver wielded the specter of Los Angeles’ smoggy, congested suburbia like a cudgel against pro-freeway politicians. This debate culminated in a 1972 provincial election that put an end to any large-scale freeway efforts. With freeways a political nonstarter, and urban growth and congestion getting worse, the only practical option was better transit. The question was, what form should that transit take?”[lix]

The answer to this question turned out to be the SkyTrain.

The SkyTrain, “the western world’s longest automated metro”[lx] is also an almost-entirely elevated line. These two circumstances together show just how unique Vancouver’s rapid transit system is: on the one hand, it represents the most advanced transportation technology of its time; on the other hand, it’s a bit of a throwback to the earliest days of North American metro lines.

Berman writes:

“. . . it was a natural choice to build elevateds before World War I, when speed and construction cost were paramount concerns. But despite their utility . . . elevateds had such a bad reputation that cities spent huge sums to replace otherwise functional elevated lines in the mid-20th century. From the 1920s onward, large-scale elevated construction fell out of favour in North America and never really returned, except where required by reasons of geology or economy. Vancouver’s SkyTrain, the Western world’s longest automated metro, is the exception to this rule.”[lxi]

What made the SkyTrain exceptional? The fact that the system was developed relatively late turned out to be a great stroke of luck. The reason elevated lines had begun to go out of fashion was that “they belched coal smoke into the air, and rained sparks, grease, and occasionally parts onto the streets below.”[lxii] But this was in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By the 1980s, new technology made it possible for elevated lines to become viable again – and some of the very newest of this new technology was being developed right here in Canada.

The Intermediate Capacity Transit System (ICTS) had been developed at the behest of the Ontario government, specifically with mid-sized cities in mind. As described by Jake Berman,

“Broadly speaking, ICTS was an evolutionary improvement of the technologies used with BART [the Bay Area Rapid Transit System, operating in the San Francisco Bay Area], scaled down to fit the needs of smaller cities . . . while BART’s trains were run by a central computer, BART still required a driver to open and close train doors. ICTS . . . was sophisticated enough not to require a driver at all.”[lxiii]

In addition to being automated, ICTS’s trains were also shorter and lighter, and thus able to run more efficiently on elevated rail lines. Unfortunately, the system had no precedents, as it had never been implemented in the real world before.[2] In this respect, ICTS was at a disadvantage when compared to the more traditional light rail transit vehicles which had become a standard solution for mid-sized cities by the 1970s.[lxiv] Despite the unknowns, Vancouver would ultimately decide to use ICTS technology in the development of SkyTrain’s ALRT (Advanced Light Rapid Transit) system.[lxv]

By the time this piece comes into print, the SkyTrain will be forty years old, almost to the day. The system’s initial line ran 21 kilometres from Vancouver to New Westminster, and the train’s inaugural journey took place on the morning of December 11, 1985.[lxvi]

That day’s Vancouver Sun ran a special profile on the SkyTrain, which included a brief history of rail transit in the Vancouver area, snapshots of various SkyTrain stations (Burrard Station – “the design centrepiece [of] . . . the system”; “tiny” Edmonds station, built as the budget was running out; “almost invisible” Main Street Station, fashioned so as not to obstruct a magnificent mountain view), [lxvii] and a number of advertisements, congratulating BC Transit on behalf of the various businesses who were involved in SkyTrain’s implementation. This profile, though positive, was cautious in places:

“No one questions that the technology of the advanced light rapid transit is as new and Canadian as today’s paper. But the jury is still out on whether ‘new’ also means efficient, reliable, and suitable for Vancouver. Critics have called the system a lemon, a pig in a poke, and a turkey on stilts. Admirers say it’s the ‘space shuttle’ of urban transportation.”[lxviii]

Despite uncertainty about the new technology, ICTS’s Vancouver iteration was a success. As Jake Berman writes: “Expo 86 went off without a hitch . . . ICTS ended up as a commercial success, and it is now in use in a half dozen other places outside Canada.”[lxix]

The original SkyTrain line (later renamed the Expo Line) was expanded in 1990 and 1994. The Millenium Line, first opened in 2002 and extended several times since, runs from Vancouver Community College to Coquitlam. The Canada Line, stretching from Vancouver to Richmond, first opened ahead of the 2010 Winter Olympics.[lxx]

Of the system’s launch, BC Premier Bill Bennett said: “It is proof that British Columbians and Canadians, using technology developed right here in Canada, can show the way and lead the world.”[lxxi]

Vancouver’s SkyTrain is something of an accident of history. Constructed long after elevated trains had gone out of style, it might well never have existed at all if not for the fact that it was so slow in coming.

Conclusion

WHAT DO WE THINK ABOUT when we think about public transit? What images do our minds conjure? The answer really comes down to the specific city and particular neighbourhood you live in. That said, I’d argue that metro systems (in all their variety) represent the last stop, the ultimate gesture that a city can make in committing to the development of public transit. The construction of these systems can be messy, expensive, and patience-trying. But, in the three cases we’ve talked about here, I think the consensus is that we’re glad they exist. Whether steel-railed or rubber-tired, underground or elevated, automated or not: our cities are richer for them.

- [1] A bit of incidental historical context: this announcement appeared adjacent to a review of the newly published English translation of Anne Frank’s diary.

- [2] By the time the SkyTrain launched in December 1985, the new technology had been used on the Scarborough RT in Toronto.

- [i] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “London Underground”. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/London-Underground. Accessed October 25, 2025.

- [ii] Wickson, Ted. Preface to The TTC Story: The First Seventy-Five Years by Mike Filey (Toronto: Dundurn Press Limited, 1996), 7.

- [iii] Ibid., 7.

- [iv] Filey, Mike. The TTC Story: The First Seventy-Five Years (Toronto: Dundurn Press Limited, 1996), 23.

- [v] Ibid., 53.

- [vi] Ibid., 131.

- [vii] Berman, Jake. The Lost Subways of North America: A Cartographic Guide to the Past, Present, and What Might Have Been (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2023), 211.

- [viii] Filey, The TTC Story, 70.

- [ix] Ibid., 49

- [x] Ibid., 67.

- [xi] “‘Statement of Policy,’ Rapid Transit for Toronto, Toronto Transportation Commission, 1945, City of Toronto Archives, TTC reference materials, Box 3,” as quoted on “Canada’s First Subway: Why a Subway?” Toronto.ca. https://www.toronto.ca/explore-enjoy/history-art-culture/online-exhibits/web-exhibits/web-exhibits-transportation/canadas-first-subway/canadas-first-subway-why-a-subway/. Accessed October 25, 2025.

- [xii] “Canada’s First Subway – Construction Begins.” Toronto.ca. https://www.toronto.ca/explore-enjoy/history-art-culture/online-exhibits/web-exhibits/web-exhibits-transportation/the-ttc-100-years-of-moving-toronto/canadas-first-subway-construction-begins/. Accessed October 25, 2025.

- [xiii] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “London Underground”. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/London-Underground. Accessed on October 25, 2025.

- [xiv] “Canada’s First Subway: Underground Downtown.” Toronto.ca.

- https://www.toronto.ca/explore-enjoy/history-art-culture/online-exhibits/web-exhibits/web-exhibits-transportation/canadas-first-subway/canadas-first-subway-underground-downtown/. Accessed October 25, 2025.

- [xv] “Page 10.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971), 16 June 1952, 10. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.torontopubliclibrary.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/page-10/docview/1418597092/se-2. Accessed October 27, 2025.

- [xvi] “Page 7.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971), 21 June, 1952, 7. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.torontopubliclibrary.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/page-7/docview/1434557977/se-2. Accessed October 27, 2025.

- [xvii] “Page 5.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971), 28 July, 1953, 5. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.torontopubliclibrary.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/page-5/docview/1434434501/se-2. Accessed October 27, 2025.

- [xviii] Bradburn, Jamie. “‘Goodbye Traffic Congestion’: 70 years ago, Toronto welcomed the Yonge subway line.” TVO.org. 2 April, 2024.

- https://www.tvo.org/article/goodbye-traffic-congestion-70-years-ago-toronto-welcomed-the-yonge-subway-line. Accessed October 27, 2025.

- [xix] Filey, The TTC Story, 85.

- [xx] “Page 21.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971), 22 Dec, 1953, 21. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.torontopubliclibrary.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/page-21/docview/1434052252/se-2. Accessed October 27, 2025.

- [xxi] Filey, The TTC Story, 87.

- [xxii] “Canada’s First Subway: Open for Business.” Toronto.ca. https://www.toronto.ca/explore-enjoy/history-art-culture/online-exhibits/web-exhibits/web-exhibits-transportation/canadas-first-subway/canadas-first-subway-open-for-business/. Accessed October 25, 2025.

- [xxiii] Filey, The TTC Story, 87-88.

- [xxiv] Bradburn, Jamie. “Toronto Subway.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/toronto-subway. Accessed October 25, 2025.

- [xxv] Filey, The TTC Story, 111.

- [xxvi] Ibid., 114.

- [xxvii] Ibid., 129.

- [xxviii] Jamie Bradburn. “Toronto Subway.” The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- [xxix] O’Hearn, Walter. “Toronto Subway System Gem-like Production.” Montreal Star, Wednesday March 31, 1954, 24.

- https://www.newspapers.com/image/742021182/. Accessed October 30, 2025.

- [xxx] “Ranking of the 10 most populated municipalities, 1901 to 2021.” Statistics Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/dv-vd/ribbon-ruban/index-eng.cfm. Accessed October 28, 2025.

- [xxxi] “Ranking of the 10 most populated municipalities, 1901 to 2021.” Statistics Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/dv-vd/ribbon-ruban/index-eng.cfm. Accessed October 28, 2025.

- [xxxii] “Page 6.” Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971), 28 July, 1950, pp. 6. ProQuest, https://ezproxy.torontopubliclibrary.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/page-6/docview/1432695774/se-2. Accessed October 28, 2025.

- [xxxiii] “Drapeau Asks Montréal, Toronto to set Aside ‘Burning Envy.’” The Montreal Star (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) · Tue, Jun 7, 1955. https://www.newspapers.com/image/743178628/. Accessed October 25, 2025.

- [xxxiv] “100 Years of History: Secrets of the Mount Royal Tunnel.” Réseau express métropolitain. https://rem.info/en/news/secrets-mount-royal-tunnel. Accessed October 30, 2025.

- [xxxv] Berman, The Lost Subways of North America, 124.

- [xxxvi] Ibid., 124.

- [xxxvii] Ibid., 123.

- [xxxviii] Clairoux, Benoit. Raconte-Moi Le Metro de Montreal (Montreal : Petit Homme, 2016), 25-26.

- [xxxix] Ibid., 7.

- [xl] Berman, The Lost Subways of North America, 223.

- [xli] Clairoux, Raconte-Moi Le Metro de Montreal, 31.

- [xlii] Berman, The Lost Subways of North America, 223.

- [xliii] Chevalier, Willie J., McGillivray, Brett, Felteau, Cyrille. “Montréal”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 22 Oct. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Montréal. Accessed 23 October 2025.

- [xliv] Clairoux, Raconte-Moi Le Metro de Montreal,29-30.

- [xlv] Ibid., 54-55.

- [xlvi] Ibid., 58.

- [xlvii] Ibid., 65-66.

- [xlviii] Berman, 123.

- [xlix] “Métro history” Société de transport de Montréal. https://www.stm.info/en/about/discover_the_stm_its_history/history/metro-history. Accessed October 30, 2025.

- [l] Clairoux, Raconte-Moi Le Metro de Montreal, 50-51.

- [li] “Métro history” https://www.stm.info/en/about/discover_the_stm_its_history/history/metro-history. Accessed October 30, 2025.

- [lii] Berman, 225-227.

- [liii] The Vancouver Sun (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) · Wed, May 7, 1980 · Page 5. https://www.newspapers.com/image/493884376/. Downloaded on Oct 18, 2025.

- [liv] British Columbia Electric Railway Company. “Twenty Nine Years of Public Service.” B. [Vancouver] : [British Columbia Electric Railway Company], 1926. Original Format: University of British Columbia. Library. Rare Books and Special Collections. HD9685.C3 B692. Web. 31 Oct. 2025. <https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/bcbooks/items/1.0376496>. BC Historical Books.

- [lv] Maiden, Cecil. Lighted Journey : The Story of the B.C. Electric. (Public Information Dept., British Columbia Electric Co., 1948), 35-47. https://search.worldcat.org/title/2777094.

- [lvi] Berman, The Lost Subways of North America, 23.

- [lvii] Hatanaka, Risa. “Streetcars before Buses: British Columbia Electric Railway.” UBC.ca. https://digitize.library.ubc.ca/digitizers-blog/streetcars-before-buses-british-columbia-electric-railway/. Accessed October 30, 2025.

- [lviii] “Our History.” BC Transit. https://www.bctransit.com/about/history/. Accessed October 30, 2025.

- [lix] Berman, The Lost Subways of North America,123.

- [lx] Ibid., 21.

- [lxi] Ibid., 222-223.

- [lxii] Ibid., 222.

- [lxiii] Ibid., 225.

- [lxiv] Ibid., 225.

- [lxv] Russwurm, Lani. “SkyTrain.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published March 10, 2016; Last Edited December 16, 2019. Accessed October 30, 2025.

- [lxvi] Farrow, Moira and Sarah Cox. “Glitter, Bands and Balloons.” The Vancouver Sun, Wednesday December 11, 1985, 1. Accessed October 30, 2025.

- [lxvii] “From Bright, Airy to Almost Invisible” The Vancouver Sun, Wednesday December 11th, 92.

- https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-vancouver-sun-from-bright-airy-to-a/61709419/. Accessed October 30, 2025.

- [lxviii] “It Began with a Cancelled Freeway.” The Vancouver Sun, Wednesday December 11th, 95. https://www.newspapers.com/image/495368566/.

- Accessed October 30, 2025.

- [lxix] Berman, 227-229.

- [lxx] Russwurm, Lani. “SkyTrain.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published March 10, 2016; Last Edited December 16, 2019. Accessed October 30, 2025.

- [lxxi] Farrow, Moira and Sarah Cox. “Glitter, Bands and Balloons.” The Vancouver Sun, Wednesday December 11, 1985, 1. Accessed October 30, 2025.

Anthony Salvalaggio is one of the editors of Toronto Journal.