All those motorists sitting at traffic lights cursing, should realize that it is not Hydro-Quebec’s fault.

– Hydro-Quebec, 1989

Montreal, Quebec, March 13th, 1989, 3:45am

CAMILLE WAS STARTING to regret her choices. Okay, maybe not starting. Something like finishing. There had been a journey, and the destination was regret. She was the sad drunk in the corner. It had worn off just enough for the real world to come seeping through. Before, all she had to do was let go, to feel the pulsing of the bass climb up through her feet, crawl through the nerves that snaked their way up her legs and chest, until it was personally beating her heart like a hand wrapped tightly around it. She didn’t even care to worry what would happen if it stopped squeezing. She wasn’t Camille anymore; she was part of the them that crowded the dance floor.

Now she was just Camille again. The same Camille who had built a perfect precarious life for herself, piece by piece. Now the flashing lights did nothing but give her a good view as it came shattering down around her. They were frantic, jerky, only shedding light on one small scene at a time. A man and a woman were dancing energetically, stealing kisses between twirls. Another woman was searching the floor for something. Two men were arguing loudly at the bar. She wanted to leave.

Henri had offered to walk her home, but she didn’t want to deal with his conneries. She thought that three years was more than enough, that she could trust him, but clearly she was wrong. And now what was she supposed to do? Go to work tomorrow like nothing happened? She imagined staying here at the Déjà Vu. An appropriate name. The last few years, she’d felt like she’d been reliving the same moments over and over again.

When she confronted him earlier that night, after she’d scared away the new girl on his arm, Henri had accused her of being already taken. He said he never had a chance, that she spent more time with Châtelaine than she ever spent with him. She hated that her first instinct had been to apologize. She didn’t want to entertain the possibility that he was right.

The Déjà Vu was a place for beginnings and endings. It lived up to its reputation well.

She could hear – just barely – the sound of the toilet flushing behind the door of the unisex bathroom at the back of the bar behind her. She turned in time to see it swing open, and a young man stepped out. She let him pass, then moved to go in herself. It wasn’t ideal, but at least it would be a respite from the lights and sounds and smells of the bar, a chance to collect her thoughts in peace.

She grabbed the door handle, trying to ignore how unusually warm the metal felt.

And that’s when the lights went out.

The silence was eerie. It was like someone had flipped a switch. In an instant and with what Camille may have imagined to be a sharp click, the bright lights snapped off and the music fell silent. There was a moment of stillness, and then everyone seemingly started talking at once. She could feel the movement all around her and was suddenly glad that she had been hiding out in a quiet corner.

There was a sharp tap on her shoulder, and she jumped, yelping shrilly. She felt her elbow connect with something and heard a soft thump beside her.

“Crisse de câlice de tabarnak d’esti de sacrament!” she swore, using the words to release her now-useless adrenaline as if it was a physical entity escaping through her mouth.

“Sorry!” a voice called from below her. Her eyes were adjusting to the dark and she could make out a man’s silhouette. She must have accidentally caused him to trip in her panic. “I didn’t mean to scare you. I was just trying to get around you.”

She offered the stranger her hand, and he took it, pushing himself back up to a standing position.

“Thanks.”

“You okay?”

“Yeah.” He stood there, as if waiting for her to turn or walk away.

“Where are you even going? The door’s the other way.”

“Um.” He stood awkwardly for a second, as if trying to decide something. He squinted at her in the darkness. “There’s an underground tunnel downstairs. It leads to a parking lot down the street. Probably much easier to get out that way than trying to get through that.”

He motioned towards the main – and busiest – part of the club, where Camille could barely make out a clump of person-shaped shadows, waved and walked away.

Camille turned towards the main exit. She wanted to keep walking until she was back home, huddling under a pile of blankets and cursing at her useless, sputtering radiator. But that would mean she would have to go through that sweaty mass of people first. She was all but trapped in a hot, dark, room full of scared, drunk people.

She turned back in the direction the stranger had gone – the lesser of two evils. From one basement to another. She was starting to think this was the story of her life.

“Wait!” she called out. “Where’s this tunnel of yours?”

Chapais, Quebec, March 13th, 1989, 4:15am

STELLA WOKE because she was cold. The world outside was always cold this time of year. But the little house was well-built. It was one of those old houses from back in the 20s, when the town was first built, before it was even a town. Sometimes she would hear her friends’ parents complaining about the cold, how they always had to wear layers indoors, and her mother would pat the walls of their house proudly.

“They just don’t build them like they used to,” she’d always say.

She was right. Stella never felt cold at home. They lit the fireplace in the evening and turned up the radiator when they went to bed. Stella crawled every night into a veritable fortress of thick, colourful blankets, into a pocket of such powerful warmth that she would always end up shedding her PJs like a pelt. She imagined this is how she might have felt as a baby in her mother’s womb.

But now she was cold, so cold that it seemed to reach out to her with its icy tendrils, to worm its way under her blankets, to poke at her soft flesh as if to say, “Wake up. There’s something I want to show you.”

It was a tough choice. If she left her bed, then her mother would literally kill her, but if she didn’t move, she might freeze to death. At least her mother would make it quick.

She leaned over, sweeping her hand across the floor in a blind search for her discarded PJs. She threw them on, shivering involuntarily as she exposed more of her skin to the air outside the blankets. There was a faint glow peeking through her curtains, even though the alarm clock by her bed said it was still nighttime. Maybe the moon was really bright tonight.

Stella reached for the lamp behind the alarm clock and flicked the switch with a click that cracked through the frigid air like a whip. No response. She tried again. On, then off. On, then off. No light.

The lump in the bed across the room groaned. Great, now Mathilde was awake. Her window for sneaking around had passed.

“What are you doing?” Mathilde whined. “What time is it?” She blinked in the light that was still peeking through the curtains. “Why didn’t the alarm go off?”

“Because it’s not time to wake up, niaiseuse.”

Mathilde stuck her tongue out. Then she saw the time.

“Oh my god, it’s so early. Mom said you had to stop waking me up on school nights. The things I do actually matter now. She’s so gonna have le feu au cul.” She jumped out of bed to go tattle, like the annoying narc that she was, but she froze halfway to the door as the cold suddenly hit her. “Saint ciboire, it’s so cold!”

Mathilde was only three years older than Stella. But those three years made a lot of difference. For one thing, she had just started high school that year, and that meant that she’d discovered swearing. Their mother hated it when she swore, so she made a game of it, trying to see how much she could contaminate Stella’s ears before she was caught.

The other thing was that Mathilde was old enough to remember their father before he died in the great New Year’s fire that decimated the old Opémiska Community Hall, back when Stella was only three years old. Mathilde remembered what Christmas looked like, the way it was supposed to be, without the shadows. But most important of all, there were times when Mathilde and their mother got that same look in their eyes, and sometimes it was like they were communicating, speaking a language that Stella would never understand. Nobody ever spoke of their father, but Mathilde and her mother knew things, and they kept those things locked away, so close, but boarded up tight behind two sets of baby blue eyes. Sometimes Stella hated her brown eyes.

The two sisters were still wrestling with their third layer of clothing when their mother burst into the room, her light brown hair messy with sleep. She had dressed more hastily than the girls; she wore a fleece and an old puffer jacket thrown on over her PJs. She was holding an emergency flashlight, which lit up her face like a beacon. There were dark circles carved into the soft flesh under her eyes.

“Oh good, you’re both awake.” Stella and Mathilde exchanged looks, temporarily putting their differences aside in an attempt to escape their mother’s wrath. They had both been half expecting a slap on the bottom and a talking to, which would have stung a lot more in the freezing air.

“What’s happening?” Mathilde asked. “I have a math test tomorrow.”

“The power’s out,” their mother said. “Come on, Mathilde, help me empty the fridge. We’ll bury the meat and cheese in the backyard. And you–” She turned to Stella. “Go get the keys and start heating the car. We’ll wait in there until it warms up a bit.”

The two girls stood and stared, trying to process the situation. It was cold and dark, and they were still blinking the sleep out of their eyes.

“Come on,” their mother snapped her fingers. “Move it, allez-y.”

And the spell was broken. Mathilde followed their mother to the kitchen, and Stella was left all alone.

They had taken the flashlight; in their rush, they hadn’t thought to make sure Stella had a light of her own. But she didn’t need it. Light still poured through the spaces between the thick curtains.

Last year, a guest speaker had come to her school to talk about what to do in case of a blackout. They happened all the time, especially as far north as Chapais. So Stella had no excuse; she knew very well that the curtains ought to stay drawn to save heat.

Except the light reminded her a little of the UFOs she sometimes saw on TV. How would she feel if she ended up being that girl who could’ve helped make first contact with aliens but didn’t because she was too busy following the rules?

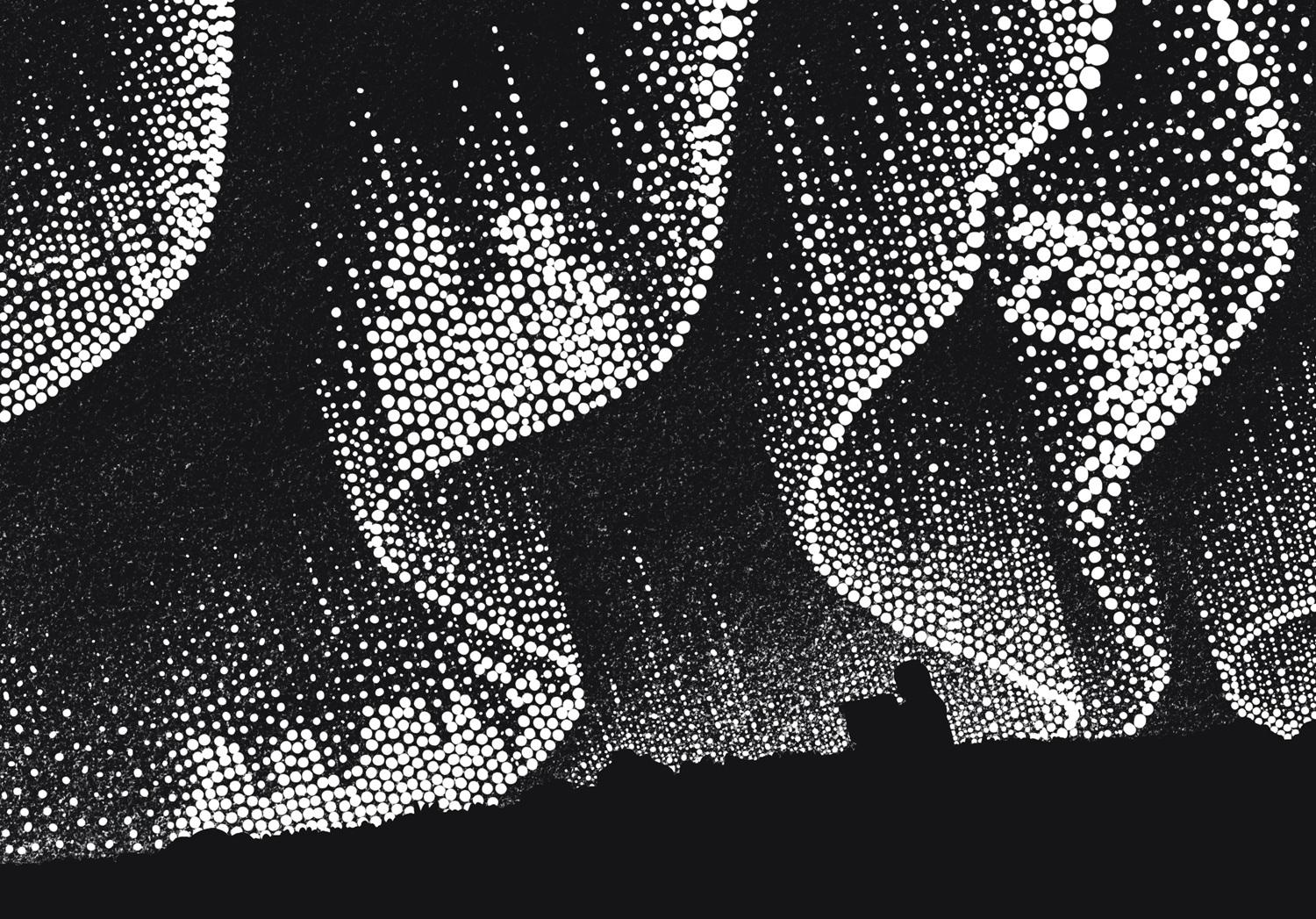

She drew back the curtains. It wasn’t a UFO. It was better.

She launched herself through the door and into the kitchen. “Maman! Maman!” Mathilde and her mother stood frozen, their hands full of the food they had just been about to take outside.

“What? Why aren’t you setting up the car?”

“Look, Maman,” Stella said, gesturing towards the backdoor, “there are lights in the sky.”

Lights of every imaginable colour were issuing from the southern heavens, one colour fading away only to give place to another if possible more beautiful than the last, the streams mounting to the zenith, but always becoming a rich purple when reaching there, and always curling round, leaving a clear strip of sky, which may be described as four fingers held at arm’s length. [. . .] The rationalist and pantheist saw nature in her most exquisite robes, recognizing the divine immanence, immutable law, cause, and effect. The superstitious and the fanatical had dire forebodings, and thought it a foreshadowing of Armageddon and final dissolution.

– CF Herbert, Eyewitness,

Rokewood, Victoria, Australia, 1859

Whapmagoostui-Kuujjuarapik Research Complex, Quebec, March 13th, 1989, 4:25am

EDOUARD COULDN’T SLEEP. There was something different in the air, besides the usual concerns about the melting ice. Something he couldn’t place his finger on. Something that left him tossing and turning in the thick dormitory sheets.

There had been something wrong with his instruments when he did his regular nightly check. This wasn’t unusual; things went wrong all the time up here. Not in big ways, just little things, like an instrument going on the fritz or a phone line going down. It was different up here than it was back at Laval in Quebec City. He had taken on the project because he needed a change of pace, a break from the energy of the city. But this place was different in more ways than just being colder and quieter. There was something otherworldly about it, liminal.

There was a heavy thump on his door, and he jumped. He checked the time, sighed, and padded over to see who it was. Kanti stood awkwardly outside his door. She was still wearing her night clothes, so it probably wasn’t an emergency.

“What is it?” he asked.

“Sorry to wake you,” she said. She’d grown up nearby in Whapmagoostui and was much more used to the place than Edouard was. He always caught her rolling her eyes when he made a comment about the quiet or about the instruments. “There’s been a pretty big disturbance in the Hydro-Quebec power-grid. It shouldn’t affect us since we’re off the grid, but I thought you’d like to know.”

“Thanks,” Edouard said, “I’ll make sure to keep an eye on it.” He made to close the door but stopped when he noticed that Kanti hadn’t moved. “Something else?”

“I should tell you there’s an aurora outside,” she said. “In case you want to go see it. This one’s really pretty.”

Edouard had to admit that it was tempting, as auroras always were. They carried a mystique that didn’t go away, even after he moved from the big city to the arctic circle. But he had a big day tomorrow and a lot to do. He needed his rest. Besides, up here, auroras were a dime a dozen.

“Thanks for telling me,” he said. “Maybe next time.”

Kanti shrugged and left, presumably to go back to her own bunk. Edouard tried to go back to sleep but found that it still wouldn’t come. He was stuck, staring at the wall, then the ceiling. He rubbed his eyes until bright colours burst across his eyelids and swam across his vision when he opened them, as if the aurora had invaded the building through the blank wall. He got up and moved to take a Nytol but stopped with his hand halfway to his mouth. If Kanti thought it was pretty, then there might be something to it. He had a feeling he wasn’t going to get any sleep anyway.

The sky was on fire, almost literally. Red and pink sheets of plasma streamed out in a circle from directly overhead, with blue-white streaks like xenon flashes occasionally strobing across the sky. We could literally hear a sizzling, cracking sound around us.

– Dan Maloney, Eyewitness, 1989[1]

Chapais, Quebec, March 13th, 1989, 4:30am

THE SKY WAS ON FIRE. It was better than fireworks on Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day. Stella always got the impression that the fireworks were malevolent invaders, polluting the sky. That there were some places where man-made things were never meant to go. These lights were a part of the sky. They were welcome visitors. They swirled and twisted and shone, and their reflections bounced in the snow that blanketed the ground. Mathilde was quiet for once in her life, her face tilted upwards. The lights danced across her face, constructed kaleidoscopes in her eyes. Stella hated the thought that they might have penetrated the baby blue walls, that they might already know her sister better than her. But they were too beautiful to hate.

Their mother came back down the street to meet them. She huffed with the effort of trudging through the night’s fresh snowfall. There was someone else with her: Mme. Levesque, a family friend. They would often come home from school to find her chatting with their mother in the kitchen, helping her with the cooking or the dishes. Sometimes she ate with them, too. She baked them loaves of fresh bread and knitted scarves and shawls and sweaters for the girls. Her husband had also died in the fire, but before they could have any kids. Their mother always said that she hung around so much because she had nothing better to do.

“Why aren’t you two in the car?” their mother asked. She had left them with instructions to get inside and try to salvage a few hours of sleep. Stella pointed to the sky by way of explanation.

“It’s an aurora.”

“Yes, I know, ma belle. I didn’t think we could get them this far south.” She exchanged a look with Mathilde, another secret communication that Stella would never decipher. “Why don’t you at least try to go to sleep? So you’re ready for the big math test.”

“She probably doesn’t have to worry about that,” Mme. Levesque chimed in. “Everyone up and down the street’s lost power. Probably the whole town, knowing the maudit Hydro-Quebec. I doubt anyone’s going to school tomorrow.”

“No school?” Stella’s ears pricked up. She might be up, standing outside at 5 o’clock in the morning, watching an aurora that shouldn’t exist, but no school? No school was serious business.

She knew that Mathilde probably didn’t feel the same way. Everyone always told her that she would make a great lawyer someday. Stella had always taken that to be a polite way of saying that she was annoying, but Mathilde really took it to heart. As soon as she entered high school, she had decided that she would get good grades, so she could go to the best CÉGEP – or as their mother said, the closest one – then on to McGill University, then on to law school. Stella sometimes caught her practicing English phrases in front of the mirror. Their mother didn’t have any objections to these developments, but Stella did. All it did was make her sister even more insufferable than before.

But shockingly, Mathilde didn’t cry about all the wasted studying or insist that they go to bed just in case. “If there’s no school, then can we stay up? Please? Just to watch?”

Mme. Levesque laughed. “The girl has her priorities straight. You should let them stay out. When are they ever going to get to see an aurora again?”

Their mother nodded. “Alright. Just be careful. And stay put. Mme. Levesque and I are going to check up on the neighbours. We’ll be right back.”

Stella and Mathilde nodded, an unlikely alliance for an unlikely morning. The two women walked away, leaving the girls to sink to the ground where they could burrow into the soft snow and fix their eyes resolutely to the swirling sky without straining their necks.

But Stella was young and unused to silence.

“Mathilde?”

“What?”

“When you’re done with university will you come back here?”

“Obviously. I’m going to be the best lawyer in all of Chapais.”

“That won’t be very hard. You’ll be the only lawyer in Chapais.”

“Shut up.”

Stella shut up. Despite all her teasing, she hoped her sister would always come back home.

“Hey, Stella?”

“What?”

“When I’m in university, you should come visit me. I’ll show you around.”

“Okay.”

And that was that. They lapsed into a more comfortable silence.

For some reason, Stella’s mind wandered back a few years, to this Cree girl who used to go to her school. She would stand off to the side whenever they played cowboys and Indians. She would cross her arms and say that she didn’t like the word “Indian.” When Stella had asked her mother about it later, she had scoffed and waved her hand as if shooing away an annoying fly.

“Words are words,” she’d said.

“Then why do you yell at Mathilde when she says bad words?” Stella had asked. Her mother had glared at her then and told her to stop thinking already and just go outside and play.

The Cree girl left when her family moved to Chibougamau up north. Stella brought her some cookies she’d helped her mother bake, along with a little card saying, “We’ll miss you!” She tried to get her other classmates to sign it, but not very many of them were interested, so she drew a big smiley face in the white space. She didn’t know the girl very well, but they’d been on the same team during snowball fights sometimes, so she asked why she was leaving. The girl said that her parents wanted to help build another city, just for Cree people. The idea had confused Stella.

Stella’s teacher once said that most Québécois had at least a little First Nations blood in them. She said it was because the French were lovers, unlike the British.

Stella wondered if she and the Cree girl had a common ancestor, from a time long ago. She wondered if the branches of light in the sky reached all the way to Chibougamau, stretching beyond her sight. It was impossible to tell who they touched or who touched them.

There was a light chatter in the air, now. Word was spreading, and people were starting to come out of their houses. They would gawk for a few minutes, then disappear back into their homes to dig out their folding beach chairs, which were tucked away for the winter, usually only to be brought out for beach days at Lac Cavan. Now most of the town was outside, set up on their lawns. Some mingled and socialized, but most sat still, their faces glued to the marvel in the sky.

Her mother and Mme. Levesque were back, standing close behind the two girls, speaking in low whispers that nevertheless traveled far in the crisp air. Stella strained her ears to listen.

“The reds, they remind me of the fire, without the smoke,” Mme. Levesque was saying. Stella heard her mother hum in agreement. “This might be the first time the entire town’s come together like this since then. At least, in such numbers.”

“Maybe it’s for the best,” her mother whispered. “Maybe it’s cathartic, like they’ve all come back to say goodbye.”

In the distance, Stella could hear people crying. It wasn’t the sad kind of crying, but it wasn’t the happy kind either. She wrested her eyes from the lights and looked back at her mother. Her eyes were glistening.

She noticed Stella. “It’s beautiful, isn’t it?”

Stella nodded. Her mother seemed to wrestle with something in her mind. Then she lowered herself down with a soft groan, sitting right between her two daughters. Stella felt a sudden heavy, comfortable warmth across her back and realized it was her mother’s arm. She leaned in, seeking the warmth and the comfort. It was better than the womb she’d built atop her bed. It was as close to the real deal as she was going to get.

Mathilde was doing the same thing on the other side. Mme. Levesque had moved away to talk to the neighbours, perhaps sensing the intimacy of the moment. Stella turned towards her mother’s face. It bore the universal awe that had infected the town, but it was aimed at Stella, not at the sky. Stella looked back into those eyes, and she felt something unlock, slowly click open. She pushed the door aside. Behind it, she found love.

Montreal, Quebec, March 13th, 1989, 5:00am

THE STRANGER was too talkative for Camille’s liking. He was a few years younger than her – mid-twenties, she guessed – though maybe he just looked younger because he was cleanshaven. He had introduced himself as “Jules,” but he pronounced it like an Anglo, with an audible “s” at the end. She hadn’t offered her own name, and he hadn’t asked.

The entrance to the tunnel had been hidden away inside an employee-only area. The emergency lights – one of the many safety features the club lacked – had already turned on inside the tunnel. They bathed the space in a deep orange light so dim that it made everything look grey. But it was enough for them to make their way down the stairs, their arms extended to feel for the walls and their steps slow to avoid tripping on unseen obstacles.

“So you’re not from around here, then?” Camille asked. She didn’t actually care. She just wanted to focus his chatter.

“No, I’m from Toronto.” Camille groaned in the obligatory way. “Yeah, yeah, I know,” he said. “But really, Toronto’s not so bad. Or maybe I’m just used to it. I like it here too, though. I came to do some graduate work at McGill, but I think I might stay after.”

Camille smiled and nodded. She tried hard not to admit to herself that she liked the company, especially since he seemed to expect nothing from her in return.

“You know what this reminds me of?” he continued. “There was this time, back in Toronto, when the power went out, kind of like this. I was maybe nine or ten years old. No one went to school that day, so I put on my church clothes and I got this big duffel bag and gathered up my cap gun and these walkie talkies I used to play around with my friends, and I went down to the basement without a flashlight and pretended I was a spy trying to avoid the bad guys or something. Like James Bond. I got so many bruises from bumping into things, and my mum was so mad that she had to iron my clothes again by Sunday.”

“Am I boring you?” he asked.

“No,” she said. “No, I don’t mind.”

SHE WAS ALMOST DISAPPOINTED when they finally reached the exit. They’d passed from the tunnel into an underground garage, and Camille had amused herself by playing a guessing game, as they passed each car. Who did it belong to? Where were they going next? As they approached the steps to the surface, she could hear the wail of emergency sirens, much more than usual for that time of night.

“What’s going on?” she asked.

“Maybe the power’s out city-wide,” Jules guessed.

“Then why isn’t it darker?”

Despite the late hour, light streamed down into the garage through the stairway. Maybe the dream wasn’t over yet. Camille picked up her pace, practically launching herself up the stairs to see what was going on.

“Whoa.”

“What is it?” Jules asked. He hurried to join her. He fell silent.

The streets were more alive than they should’ve been at 5am. Emergency vehicles raced up and down the streets, their sirens all screaming over each other. People gathered on the streets, bundled up in their coats. They stood in small groups, complaining about Hydro-Quebec or gawking at the scene around them.

But Camille and Jules weren’t looking at the streets. All they were looking at was the sky.

“Is that – an aurora?” Camille asked.

“I didn’t think they came this far south.”

“They don’t.” Maybe this was the universe’s way of making up for the foutue day she just had.

They stood there watching until their necks ached, until Camille felt like she’d pushed the dream all the way to its limit.

“I’d better head home,” she said.

“No, wait. Please let me walk you home. Now that there’s a blackout and everything. Just to make sure that you get back safely.” He sounded sincere, but anyone could sound sincere.

“Thanks for the offer, but I’ll be okay.”

“Please. I don’t want–”

She turned on him. “Why do you care so much anyway? What were you doing skulking around in the back corner? And why do you know about this secret tunnel?”

He paused, as if deliberating, as if weighing two options he didn’t like. Then, “My boyfriend is a bartender there.” He said it with a slight hesitation, as if even he didn’t know if he were telling the truth. “Ex,” he corrected himself. His voice was now hardened and clear. “Ex-boyfriend. He was cheating on me.”

Camille couldn’t help it. She began to laugh. “What are the chances?” She paused. “Wait, I mean, I’m sorry. It doesn’t feel very good, does it?”

Jules’s brow furrowed for a moment in confusion until he seemed to realize what she meant. That they had both had the exact same evening.

“No,” he conceded. “But you know what they say, misery loves company.”

Camille suddenly felt that he was the only person in the entire world who understood her.

“Qu’ils aillent se faire foutre,” she said.

“Yeah,” Jules smiled. “Fuck ‘em.”

CAMILLE DIDN’T GO HOME. She allowed Jules to show her this big dépanneur he had discovered, which was open 24 hours and served cheap deli food. Only in Montreal, she thought. The chicken sandwiches weren’t very hot or very fresh, but they were good enough, and soon the two of them found themselves sitting in the damp grass of a nearby park, their heads resting against the seat of a bench so they could better see the sky.

“What are you going to do tomorrow?” Jules asked.

“Probably go to work. Same old, same old.” He didn’t ask for clarification, but she felt that she at least owed him that much. “I’m an editor for Châtelaine.”

“That’s cool.”

“No, it’s not. Nobody wants to read Canadian magazines. They’re all too busy reading the American ones. Sometimes I think about moving to the States. New York City. Working for a magazine that people actually read.”

“Why don’t you?”

Yeah, Camille, why don’t you? “Well, my English isn’t great for one thing. It’s – how would you say it? – shit.”

“I could teach you. I’m training to be an English teacher. That’s what I want to do when I’m done with school. I like talking to people.”

Camille laughed. “I can tell. But seriously, you don’t have any other ambitions? How do you know that teaching English will make you happy your whole life? Or living in one place?”

“I don’t.” She could hear the shrug in his voice. “I can always do something different if I want to. Or go somewhere else.”

“Like when you’ve had enough of living somewhere where you don’t speak the language?” she teased.

“I speak French,” Jules countered, and Camille couldn’t help but laugh again.

“Okay, your French is pretty good, but your accent is de la merde.”

“Maybe you could teach me.”

“I’m no teacher,” Camille admitted, “but maybe I could.”

They lapsed into a comfortable silence. Despite the talk of future meetings, they both knew they would never see each other again. Their sudden friendship was a thing born of unreality. It existed out of time, like this moment. It would never feel real again.

The colours of the aurora twisted and blurred in Camille’s vision. A few empty tears welled lazily in her eyes, as if by obligation. They turned the sky into a splotchy supernatural sunrise, easing its way across the horizon like a drop of ink blossoming in a puddle of water.

She could fall asleep here. Maybe when she woke up, she would be a different person. A blank slate. A woman without a boyfriend, without a job, without a purpose. But she wasn’t scared. She knew that a woman who has nothing has everything.

Gatineau, Quebec, March 13th, 1989, 5:30am

JEAN-PAUL WAS WALKING by now, rolling his bike along beside him instead of riding it. It wasn’t because the snow made it difficult to ride; he was used to that. It was because he was distracted, too busy staring at the lights in the sky to focus on where he was going. And it was dangerous to lose focus on the Gatineau trails. All that Precambrian rock made for treacherous cycling.

He had woken up that morning with no power, which meant no heating, no lights, and no microwave to heat up his instant oatmeal. The smart thing to do would’ve been to take the bus across the river into Ottawa. Hydro-Quebec was singularly incompetent. It was likely that Ontario still had power.

But he didn’t like the idea of starting his morning without his daily bike ride. It was stressful being a nurse; everybody wanted a piece of you all the time. Many of his colleagues smoked or drank the stress away; Jean-Paul channeled it into pedaling, until the tightness in his chest became a tightness in his thighs. Besides, he liked the alone time.

This morning had offered him a special treat, and he hoped that it wasn’t just to prepare him for some fresh horror at work. He stopped at his favourite spot, a sudden drop-off overlooking what used to be a prehistoric sea. He tried to imagine what the aurora would’ve looked like reflecting off its vast, rolling surface. The Gatineau Hills were beautiful but dangerous. They made you feel like the speck of dust you were, like a single flash of lightning in the incomprehensibly long life of an ancient planet.

He took out his polaroid and snapped a few photos. Some of the patients he worked with would never see the sky again. It wasn’t fair for them to miss this. It was a sight that belonged to all of humanity.

O lights of the north! As in eons ago,

Not in vain from your home do ye over us glow!

– William Ross Wallace, 1859

Quebec City, Quebec, March 13th, 2015, 6pm

STELLA SAT ALONE at the small kitchen table of her city apartment, waiting for the soup to cool. It smelled good, and Stella hoped she had gotten the recipe right. Her colleague had taught her how to make it in exchange for Mme. Levesque’s bread recipe. She had called it shorba, a kind of lentil soup.

Ten years in, and she still wasn’t used to living in the city. As exciting as it was to be surrounded by a symphony of people, ideas, and cultures, Stella sometimes missed the simplicity of an afternoon spent playing tag in the snow or the comfort of her mother’s steaming tourtière. Her colleague had said that this was comfort food where she came from, and Stella had no reason to distrust her.

As she waited, she pulled out her laptop to check on her Reddit thread. The aurora she’d seen back when she was a kid had implanted itself like a seed in her mind, driving her towards the study of astronomy and all the way to Laval University, where she worked closely with NOAA to track and study geomagnetic storms.

There had been two scares in the last couple of years: a really big one in 2012 and a slightly smaller one in 2013. Both completely missed the Earth, but they got Stella thinking back to that special day so long ago.

She knew now that both aurora and blackout had been caused by a geomagnetic storm hitting the Earth. And she knew that it hadn’t been the first time, either. A similar storm in 1921 had disrupted telegraph communications across North America and Europe, and another storm in 1859, labelled The Carrington Event and known as the most powerful storm of its kind to hit the Earth in human history, created auroras that could be seen as far south as Australia and New Zealand.

She’d developed a historical fascination with these events that baffled her scientific-minded colleagues. But they conceded that her efforts were useful in helping them track the events. Her apartment was stacked with binders, filled with her collected eyewitness accounts of various storms from throughout history and across the world.

Years ago, when Mathilde was studying law at McGill, the sisters would have weekly phone calls. During one of those calls, Mathilde had told Stella something that took on a new meaning in the face of her personal fascination. Mathilde said that she had an English tutor who had mentioned also seeing the aurora in 1989, back when he was a graduate student at McGill.

The conversation had come back to her in light of a completely different one she’d had with a colleague, a veteran professor and researcher at Laval who always teased her for her fascination with the 1989 aurora, considering he’d seen many.

“They were a dime a dozen up in the arctic circle,” he’d said. “But,” he’d conceded, “this one was special. I couldn’t put my finger on it. Something kept me from sleeping that night and forced me to go see it.”

She had been so excited by the coincidence that she’d asked for permission to write down his exact words. And it got her thinking. Who else had been watching the same aurora that night? She created a Reddit thread, asking that very question and she was quite pleased with the results so far.

Floridian here. I got up early that morning to go fishing. I don’t know what it was that made me do it. I’m not a big fisherman or anything. It’s like the lights were calling to me.

. . .

I get up every morning to go biking in the Gatineau Hills. It helps clear my head. Imagine my surprise when I got a free light show to accompany me.

. . .

I’m living in Europe now with my partner, but I was still in high school back in Utah in 1989. I remember watching it on my way to school. My parents almost kept me home. They were all in a tizzy because they were convinced the Soviets had finally dropped the bomb. None of us had any idea what an aurora was supposed to look like; we never expected to see one during our lifetime.

. . .

I was a stupid young man in 1989. I was working as a bartender in Montreal. The night of the aurora, I had just made another stupid mistake. My boyfriend caught me cheating. Not like I didn’t want him to; I was doing it to make some kind of point. But I felt terrible about it right away, and it felt worse when I went outside and saw the beautiful lights, like they were mocking me. I hope he saw them. I think he really would have liked it.

Stella scrolled down to the bottom of the page. There were a few new responses, but nothing huge. She would make sure to respond to each of them by the time she went to bed that night. She wondered about the Cree girl who’d moved away. The project to build a Cree village had been a success. Stella had read all about the new Oujé-Bougoumou back in the 90s when it was officially founded and again in 2011 when they opened the revolutionary Aanischaaukamikw Heritage Centre. She knew now almost for certain that the aurora had been visible in Chibougamau. It had been visible over most of the Northern Hemisphere.

She’d drafted a letter to that girl from her class, even though she couldn’t even remember her name. For some reason, she felt it was important that it was a letter instead of an email. She included the usual platitudes, asking how she’d been and if she remembered her, and then she asked her to describe the aurora in as much detail as possible, from her perspective. Eventually she would track her down. Eventually she would dust the letter off and send it.

Last year, she had caved to the pressure and sent in her DNA for an ancestry test. Apparently, she was 10% Cree, which studies indicated wasn’t unusual for a French Canadian.

She closed the laptop. The soup must be cool enough by now. It had a strong, unfamiliar smell that drifted through the air, carried by the steam rising from the bowl. She took a tentative bite, then smiled.

Author’s Note

I became fascinated with geomagnetic storms because I love the idea of such a cosmic phenomenon connecting so many people across time and space. While I ultimately chose to focus my story on the event in 1989, my research spanned centuries of geomagnetic storms. Here’s a short selection from that research involving images and eyewitness accounts from several geomagnetic storms throughout history, including the most recent one in May 2024, which occurred only months after I finished the first draft of this story.

Ahmed, Issam. “First ‘Extreme’ Solar Storm in 20 Years Brings Spectacular Auroras.” Phys.org, 10 May 2024, https://phys.org/news/2024-05-strong-solar-storm-disrupt-communications.html.

Krisher, Tom, et al. “Federal Agency Says a Second, If Weaker, Solar Storm Surge Is Likely Sunday.” AP News, 11 May 2024, https://apnews.com/article/solar-storm-northern-lights-power-grid-disruption-eb7fabd1dfbd734a398192bf4c701ca5.

Maloney, Dan. “Lights Out in Québec: The 1989 Geomagnetic Storm.” Hackaday, 10 Apr. 2017, https://hackaday.com/2017/04/10/lights-out-in-quebec-the-1989-geomagnetic-storm/.

Phillips, Tony. “The Great Geomagnetic Storm of May 1921.” Spaceweather.com, 12 May 2020, https://spaceweatherarchive.com/2020/05/12/the-great-geomagnetic-storm-of-may-1921/.

“Chapter 1: A Conflagration of Storms.” Solar Storms, 17 Apr. 2017, https://www.solarstorms.org/SWChapter1.html.

“Solar Storm 1859.” Solar Storms, 17 Apr. 2017, https://www.solarstorms.org/SS1859.html.

Willis, David M., et al. “Auroral Observations in Finland: Visual Sightings during the 18th and 19th Centuries.” Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 37, no. 4, 1996, pp. 733–742.

[1] True eyewitness account, printed with author’s permission. https://hackaday.com/2017/04/10/lights-out-in-quebec-the-1989-geomagnetic-storm/

Kassandra Haakman is a fiction writer currently pursuing an MFA in creative writing at UBC Okanagan. She has been previously published in 805 Lit+Art magazine and has had several of her plays produced. She is working on her first novel.