ON FRIDAY EVENINGS, Tara treated herself to a medium oxtail with rice and peas. ‘I work hard and I deserve it,’ she convinced herself, knowing the twenty-dollar meal was pricey on her monthly budget. The size was just enough to share with Lani without any leftovers except for the brown runny gravy.

By the time the 2 train screeched out of White Plains station, Tara had hopped over the slushy snow puddle at the bottom of the subway steps. She had intended to stick to her savings plan for most of the train ride. To stop by the grocery store, pick up linguini noodles, creamy alfredo sauce, a chicken breast, broccoli, and rainbow cookies and make the best out of the simplest dinner she could whip up in under an hour. But her scrunched toes had rubbed against the leather of her black boots as she shifted her weight from her right leg to the left while holding onto the rail for the one hour it took to commute from downtown. Still standing five stops before pulling into the station, Tara figured one meal wouldn’t drain her savings.

A block and a half from the station, Nyam Ya, the most authentic Jamaican food Tara could find in the eight years of living in the Bronx, was nestled between a nail salon and a beauty supply store. The storefront was so ordinary and plain that it would be easy to miss if it weren’t for the wide flatscreen hung high, displaying the menu in bright green letters. The storefront restaurant was a hole within a hole. It was one of the small, cramped shops that served a community that could find a taste of home in the food.

Once inside, Tara relaxed. The entire week had been worth standing alongside impatient customers who sucked their teeth when the cashier yelled, “Five more minutes for da’ three chicken chop suey!”

A man behind the counter looked up at her and smiled wide while he picked through the sweet chili sauce for a large piece of whiting fish.

“Back again, princess?” he said, his voice so loud that Tara was sure anyone from outside could hear.

“Roy, yuh know mi’ couldn’t finish my week without comin’ through,” she teased.

“To see me, right?”

“And to see if yuh won’t be so stingy dis time and give me more than four dry oxtails.”

“Get rid of yuh boyfriend and I’ll double it!”

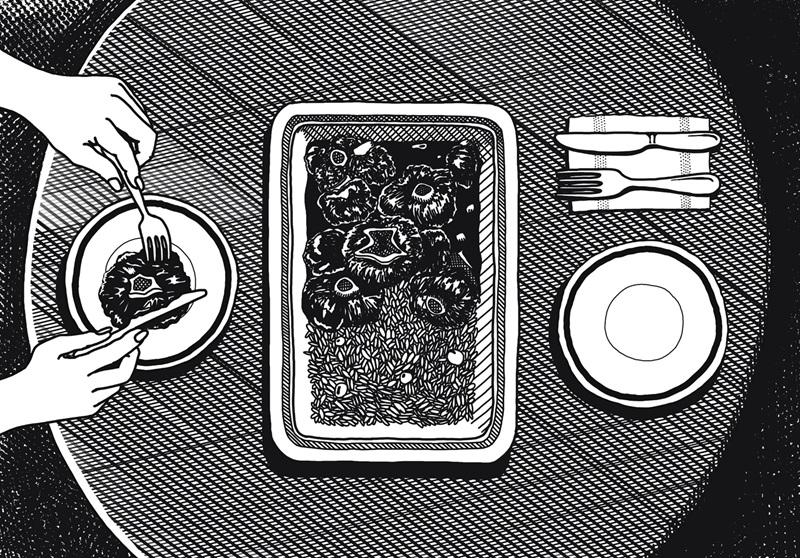

One by one, the line shortened until Tara was next to the counter inhaling the mixture of seasonings rising from the food warmers. She didn’t have to say what she wanted or how she wanted her order prepared. Instinctively, Roy piled rice and peas into a black plastic container while she watched, eager to guide him. With a long, metal spoon, he touched each oxtail for the most tender pieces. Tara counted eight in total, all medium-to-large size. Two mildly charred plantains were put at the side of the main attraction, and a cabbage mix completed the otherwise coma-inducing tower of delight.

After scribbling her number on the signed receipt as appreciation, Tara stepped into the night which wasn’t quite night yet. The greyish sky threatened darkness as the orange streetlights shone like little gemstones of fire. City noise was unlike any other noise. It was persistent and alive. It took time, but Tara had learned to ignore all the sounds. The noise had become the background music to her life. Always aware of her surroundings, especially as night closed in, what she did notice were faces.

Living near White Plains station, she always saw the same faces. She was on smiling terms with a few of the mothers who she only knew in passing, she nodded at the men in the liquor store that gambled the same ten dollars, she played nice with the mailman who never left her packages in the hallway so they wouldn’t be stolen, she listened reluctantly to huddled neighbours from other apartment buildings that complained about some boys who made a hobby out of slashing tires, and she occasionally gave a few dollars to the children lounging on the building steps to buy Italian ice cups from the corner store on a summer day. This evening, there was one face who made her curious enough to slow her natural strides and discreetly steal looks here and there.

A woman in a floral headscarf dragged her feet forward, with each step seeming heavier than the last. Fascinated without understanding why, Tara did her best to disguise her stares. She slowed her pace and stopped to pretend scroll through her phone. All to catch a glimpse of a woman who hauled a large laundry bag on her back. The floral headscarf clashed with the plain black bubbled coat that fell to the woman’s ankles. This was the second winter in a row where Tara looked down at the woman’s worn, furry moccasins with long white socks disappearing into jeans and wondered if they were the only pair of winter shoes she owned. Like always, she carried a plastic bag with detergent in one hand and a mid-sized laundry bag in the other. Every eight or so steps, the woman would stop, breathe heavily, shuffle her feet to catch her bearings, then continue.

In a way that she couldn’t describe, the woman reminded Tara of her own mother. That lingering memory of seeing her mother tear through all the elements with grit and determination to make the best of the day. The fresh accent. The outdated fashions. The blunt conversations. The not knowing a simpler way of doing things because of not having the necessary conveniences. Tara didn’t have to know this woman to understand this woman. Just the sight of her made Tara want to get close enough to savour the taste of what was familiar.

From the babysitter, Tara walked hand-in-hand with her daughter to their cramped one-bedroom apartment on the third floor. Once inside, she kicked off her boots and rubbed the soles of her feet against the carpet to ease the soreness. As soon as she took off her leather gloves, she rubbed her fingers to bring the colour back to her ebony complexion. She pulled off her hair tie and let out a deep sigh, as if freed from the tension that she had felt for most of the day.

“I hope you got the big pieces this time, Mommy!” Lani jumped and clapped excitedly.

“I got your favourite cream soda too,” Tara said. She grabbed the plastic bag and made her way into the kitchen. She opened the black container. Her nose prickled from the steam, and she closed her eyes in satisfaction. At the little round wooden table that was just big enough to fit two bodies, Tara pushed a bowl with a mash of oxtail, rice and peas, and cabbage in front of her daughter while she ate from the container.

Savouring each bite, she chewed slowly with throaty coos of approval. Halfway through the meal, as she began to pick at the rice with her plastic fork, Tara took a few gulps from a cheap bottle of pinot noir. And instead of forgetting, she remembered: her bills, her problems, her singleness, the ex who left, the simple apartment, the dead-end job, the mother she cut off, and all the childhood memories that she believed she was too mature to care about at almost thirty.

SATURDAYS WERE for mini adventures in the city, all within Tara’s price range. Cheap was best, but free was even better. A quick museum trip or browsing through Macy’s at 34th Street to stay warm would quench her need for thrill and variety. Sundays were for preparing for the work week. By ten in the morning, Tara cooked a meat lasagna that would last until Thursday. By noon, she sorted all the dirty laundry by colour and was out the door pushing a mini shopping cart to the laundromat closest to the subway station.

Bubbles & Clean was the only twenty-four seven laundromat Tara could rely on to be fully serviceable at every hour of the day. There were rarely any out-of-order signs placed above machines. Dryers were emptied of all debris every hour. Even unclaimed clothes left in carts were thrown into heavy-duty garbage bags and sat behind the counter for a month before being tossed out. For safety, the doors were locked for customers to wash and dry in peace when night approached.

Laundry bags with customer receipts were in a pile at the door. Stiff wet clothes were thrown over laundry cart hangers. Some customers folded clothes on the folding tables while others stood like zombies to watch the washing machine stop and then turn again, waiting for the right moment to pour in detergent. And other than the tumbling of clothes in dryers, the only other sound came from the children shouting at an old Pac-Man game.

Tara pulled out a twenty-dollar bill from her back pocket and forced it into the laundry card system. When the bill was accepted, she tapped her laundry card against the screen.

“Miss, cyan yuh show me how you did dat?” a voice behind her asked softly.

Nearly hunched over in her black bubbled coat, the woman who she had seen dragging her clothes to the laundromat stood before her, her broad features more pronounced under the white lights. One faded wrinkle on her forehead complemented the laugh lines beginning to set into her deep chestnut complexion. She held the laundry card in her pruney fingers, which looked as if they had wrinkled from years of strain. Her pudgy figure gave the impression of once being blessed with the right curves and softness.

“I only use quarters, but da owners seem to put a stop to dat recently.”

“Of course!” Tara said, her voice a little too squeaky. She blinked a few times to shake off the staring. “Yuh put the dollar bills where it seh ‘Insert Bill’ and when the money shows on da screen then yuh tap yuh card on da’ screen for the money to be added to da card.”

“I see.” The mysterious woman squinted her eyes for a moment before meeting Tara’s gaze with understanding.

“Yuh a real teacher,” she said with conviction. “Yuh must be a teacher for a living ‘cause mi’ would neva know yuh ah yardie too. Mi’ think seh yuh ah Yankee. Where yuh from?”

“Mi’ from West Moreland, but mi’ came to America when I was nine, so mi’ remember a little here and there.”

“Dat’s all right. You are a Jamaican always.”

“I’m Tara. I live just a few blocks away from here near the playground.”

“Oh, right by P.S. 116. Mi’ son and daughter attend dat school,” the mysterious woman said. “Call me Paulette.”

In between the mechanical tumbles of the washing machine in its last cycle, Tara spoke to Paulette like they were former classmates that had found each other again after maturity had settled in. Tara spoke of working in midtown as a receptionist at a media company. She learned that Paulette had been in the Bronx for ten years toiling away as a home health aide. Paulette spoke of Hurricane Anna which devastated Jamaica for a week’s time; a mudslide that killed two in the hillside; the killing of a schoolgirl whose body was dumped on the roadside a mile from Bluefields Beach; and an American tourist vacationing in Negril who killed a local after climbing the balcony of the Dreams resort.

“Let me find out that you are Jamaica’s number one news reporter,” Tara said teasingly.

“Nah, it’s not that,” Paulette chuckled. “Family keep me informed of these things, but I would neva go back.”

Standing next to Paulette, Tara watched her white sheets rolling around in the dryer, the glass foggy from overheating, as Paulette began to stuff her folded clothes in a laundry bag. Tara suddenly craved for home, where everything was so familiar. City life was vibrant, but harsh when doing it all by yourself. A never-ending grind of sleep, work, and money while manoeuvring around people who were a situation away from being broken. Like many others, Tara had been moulded by the beaten streets, and now found herself with unresolved issues after years of never getting ahead. She felt this unexplainable urge, from time to time, to cling to someone who could unearth her Jamaicaness when everything around her grew stale.

Tara moved closer as Paulette tied the ends of a laundry bag into a big bow. She parted her lips to speak, but stopped before she could become embarrassed by her own words. First, she practiced what to say in her head, shedding any ounce of a plea that could be traced in her voice. She didn’t want anyone to think that she needed someone even if she did. ‘Dats what men are for,’ she remembered her mother saying. But she had learned the hard way that men never quite fixed much of anything. Now, at least, she could have someone to talk to.

Two minutes were left on the dryer. Grabbing the tumbling white sheets before the last minute, Tara’s hands twitched from the heat. Paulette hoisted the bulky laundry bag on her back, and tugged at her black headscarf. Tara waited for Paulette to turn towards her.

“Let me get your number before yuh go,” Tara said casually. “What yuh usually do on da’ weekends?”

“YOU KNOW WHAT DEM SEH. All you need is a dollar and a dream,” Roy said. A devious grin spread across his face as he waved six dollars to play Powerball at the man behind the window-guarded counter.

Tara didn’t know why she had agreed to go on a date. She was more annoyed at herself for answering the phone even though his number showed up as ‘Don’t Pick Up’ when he called. Roy had just pulled down the storefront gate over Nyam Ya to close shop when Tara strolled into view. There were no other suitors to hold her attention. No would-be or could-be boyfriend who had strong arms and a vision. So far, the most decent man she could find was someone who looked like he had worked in a kitchen all his life, and not of the five-star Michelin kind.

A whiff of spicy seasonings from the restaurant appeared to mix into Roy’s soil-brown skin. His beard stuck out like a wildly grown bush. A black mole above his upper lip was in cahoots with his doll eyes to create an almost beautiful face, if it weren’t for the long scar on his right cheek and the patchy eyebrows that gave him a scruffier look. After he shoved the Powerball tickets into his back pocket, Roy grinned. Tara felt his hand press against her lower back as he guided her past the line of men who also hung onto false hope.

“Yuh still in the mood for pizza?” Tara asked reluctantly. She fought the inner voice that told her to leave, remembering that she had suggested pizza because it was in the neighbourhood, making it easy enough to down a slice if she wanted to end the date early.

“I’m still in da mood for whatever yuh in da mood for.”

Angel’s Pizza wasn’t known for selling mouth-watering, award-winning pizza, but it was good enough for something quick and cheap. Inside, covering both walls, old newspaper cutouts of ‘Best Pizza in NYC’ or ‘Top Pizza Spots in the Bronx’ were framed for credibility. Past the counter, someone flattened dough, while another stared lazily at Tara without the slightest interest in serving a customer.

Tara didn’t bother interrupting Roy as he ordered two cheese pizzas. With a heavy sigh, she slid into one of the booths, still wearing her buttoned coat and solemn face.

“Yuh seem tense,” Roy said, removing his black leather coat and tossing it in the corner as he sat down heavily.

“I just got a lot on my mind.” Tara unbuttoned her coat as if doing so was a lot of effort.

“Relax yourself,” Roy said, biting into his cheese pizza. “I know you are a busy lady. A respectable woman. Yuh nuh inna da’ nonsense. I can tell from one look in your face.”

“Yuh tell no lies,” Tara chuckled.

“Ah, she smiles! Yuh have such a sweet smile. Yuh should smile more often.”

It was Tara’s turn to bite into her cheese pizza. She chewed with pleasure, less from the pizza, and more from having someone beside her, at least for an hour or two.

A few gulps from a can of Sprite, and she felt comfortable enough to not check her phone to speed up the date.

“Roy, how long yuh deh in America?”

“Over twenty years.”

“Yuh ever think of going back home?”

“Maybe. I don’t know.” Roy dusted away the crumbs that had fallen into his beard, then wiped the grease off his fingers with a napkin and sat back. “Everyone I know wants to come here, but dem nuh know that American life is rough. It nuh easy. Every man and woman keep to themselves up here. Everyone is for themselves.”

“We work hard, but back home dem all think money grows on trees,” Tara said in agreement.

“That’s right! It’s why mi’ keep to myself now. Too many bad minded people out here always looking for something. Yuh have to watch yourself.”

“Yuh can’t be so paranoid all the time. It’s not a good way to live.”

“Yuh say that now.”

“Be positive,” Tara encouraged. “Dats what mi’ hear all the time at my job. If yuh always think something bad will happen then it will happen. We must come together as a people and look out for one another.”

“Yuh stay deh. I had a friend and back home we used to run tough together. He was da tour guide fi’ Dreams resort ‘cause him speak real nice and I was the driver. When him first come to America, I help him get situated and hook him up with a nice job in construction. Now? Him wouldn’t even fart pon me. Nuff people mi’ help when dem ah beg. Dem come here, I help dem, and not a call or a thing.”

“Not everyone is like that,” Tara said softly. “Yuh need people to get through life ‘cause life is too hard. It’s impossible to do it on your own.”

“All I know is this,” Roy began with certainty. “Never feel sorry for people because they will pass you in life and never look back.”

Tara barely listened to all of Roy’s gripes about what had happened to him or what would happen, or people who troubled him. She shrunk back to the place which held all her fears – the uncertainty of leaving home to taste freedom, then escaping into a bad relationship to be free, but learning freedom came with its own complicated set of problems. Uplifting sentiments, wherever she could find them, were the only things she had to protect herself. Tara folded her arms and looked at Roy like an old friend who she had outgrown.

“It’s getting late. I got to get back to my daughter.”

“Mi’ haffi get up early anyway fi’ make sure da’ sidewalk in front of da’ shop don’t freeze to ice after this little bit of snow.”

Tara let Roy walk with her until they reached White Plains station. They stood and waited until a late-night train squeaked in and out of the station.

“I want to see you again,” Roy said tenderly. He leaned closer until he was just a few inches away from her face.

“Next time,” Tara said with a half-smile.

She figured one mistake with a man was enough for one lifetime, and did not want to imagine what another mistake would be like.

One step after the other, nothing but her noisy black combat boots could be heard in the desolate night. At her apartment door, she fiddled with the keys caught between her numb fingers. Tara didn’t turn on the hallway light immediately, but allowed herself to bask in the darkness and accepted it as her temporary peace.

AT THE PARK next to P.S. 116, everything was buried in snow except for the benches where Tara sat close to Paulette to create warmth from their body heat. A basketball rim was covered with ice, and the net for the tennis court looked like a patchwork quilt designed with a sheet of snow cut into square cubes.

Tara watched Lani and Paulette’s two children disappear underneath the snowy hill that they slid down on heavy duty garbage bags. Laughter and playful screams were muffled by the wind. After an onslaught of flurries stuck to her coat, she glanced over at Paulette whose squinty black eyes looked forward. A black scarf covered the lower half of her face.

“Yuh daughter don’t look much like you,” Paulette said.

Tara didn’t know what to say. For a moment, she couldn’t tell if it was an accusation masquerading as an insult or a question.

“She looks like her father,” Tara said with a hint of nostalgia in her voice. “Everyone used to tell him dat she was his twin. Dat didn’t keep him around though. Him gwan about him business and hasn’t seen her since she was three.”

“Dem always gonna look out for themselves first and leave yuh with all da’ problems.”

“Who yuh ah tell,” Tara said in agreement. “What about yours?”

“One minute him deh ah Jamaica and then Canada and then Florida. Mi’ cyan keep track. Him come around off and on.”

The story was familiar to Tara. She understood the disappointment. She was no longer a lively young woman who believed anything, even her own fantasies. She was a woman who had no choice but to accept reality.

Pulled out of her own reflections, Tara’s nose tingled at a strong smell. In Paulette’s lap, wrapped in aluminum foil, was a large jerk chicken breast smothered in jerk sauce. She watched Paulette take her gloves off, and hungrily eat the skin. Paulette then tore into each piece, nibbling down to the bone.

“Dat looks good,” Tara said, blaming the indecency of not being offered a piece on not knowing any better.

“Mi’ make it often.” Paulette put the bones in the aluminum foil and threw it under the bench. “It’s simple and easy to make for da’ week. Yuh cook good?”

“Yeh mon! Mi’ make everything. Curry chicken, brown stew chicken, ackee and saltfish, and mi’ love my oxtail with rice and peas.”

“Mi nuh know how people buy oxtail now. It’s too expensive. Dem raise the price once dem see how other people buy it up. They’re too wicked!”

“Sometimes, I buy a long tail at the Caribbean Market off of Barnes Avenue. Dem will sell it for fifteen dollars,” Tara said in defense of her once-a-week craving.

“Yuh can keep dat honey. Mi’ have my bills.”

“Paulette, yuh can enjoy yourself sometimes and live a little.”

In a short time, Tara learned that Paulette was a woman who stuck to a rigid routine. No spontaneity, no newness of any kind. She held firm to her own rules, but Tara never shied away from trying to convince.

“Yuh ever spend time downtown? The Christmas tree is probably still up at Rockefeller Center. Ever seen it?”

“No. Mi’ have to be careful because da kids will ask fi’ something when dem see any Christmas tree and mi’ don’t have it right now.”

“Yuh like sweets? There’s a popular sit-down bakery in midtown. Dem have some really nice pastries.”

“Mi stick to my rum cake.”

The options had dwindled down to what was practical. Paulette crossed her arms, and her lips were pursed when she pulled her scarf down to breathe in the cold air. Tara wondered if she had asked a silly question. There was nothing special about looking at a Christmas tree no matter the many flashy decorations, and an hour train ride to try a pistachio croissant seemed like a waste of time.

“Sometimes, yuh have to focus on what’s important,” Paulette said, as if reading Tara’s mind. “Yuh waste all your money on dis and dat and then what do yuh have left?”

“Nothing, I guess,” Tara answered in defeat.

“Exactly! Right now, mi’ have nothing but myself and my two children.”

“Yuh have me now too.”

She heard Paulette snort as another strong wind sent flurries swirling over their heads.

“What yuh doin’ next weekend?” Paulette asked. Tara finally noticed Paulette staring at her curiously. “C’mon over to my place and keep me company. It looks like yuh need someone.”

TARA STOOD IN FRONT of a classic red brick apartment building with a large plastic bag of two medium oxtails with rice and peas in one hand, and Lani swinging the other. At the entrance, she pressed the buzzer next to 2F. Before she removed her finger, she heard a click. Paulette was already leaning against her apartment door wearing the first genuine smile that Tara had seen since they first met. It was also the first time she saw her without a headscarf. Five large cornrow braids came down to the nape of her neck.

“Yuh always look nice. Dat coat looks expensive, eh?”

Tara stroked the faux fur on her coat. Fiddling with the glossy black buttons, she added more sway to her hips as she walked toward Paulette.

“Dis is nothing.”

“Yuh definitely seem to like da’ finer things,” Paulette said, touching her coat. “Mi nuh know how you can afford it. Mi’ have my same black coat for years now.”

She followed Paulette into a hallway bathed in shadow except for the kitchen light that shone on the hallway closet. As Paulette kicked off her house slippers, Tara removed her black boots and motioned Lani to do the same. She inspected the cream-coloured carpet indented with footprints, battered by dust and dirty foot soles. While removing her coat, she noticed the one black leather couch in the living room, which appeared bare against a picture-less wall. A gold-framed, full-length mirror stood in the opposite corner, her own reflection warning her to not look so judgmental. Then, there was a plain coffee table with scattered workbooks and magic markers, and Paulette’s two children sitting Indian style in front of a small television. The living room was furnished only with what was absolutely necessary.

“Turn dat off and come get some of this,” yelled Paulette from inside the kitchen.

Paulette took one of the brown paper bags from Tara’s hand. “How much dis cost?” She eagerly opened the plastic container, letting the steam blow into her face.

“Not much at all,” Tara lied. She was embarrassed by the forty dollars spent. Her overindulgence in what she enjoyed once a week seemed like a frivolous extravagance.

“Mi’ nuh know how you do it.” Paulette greedily picked up a white plastic fork and began to mix the rice and oxtail gravy. “Mek mi’ get my pocketbook and I’ll give you half. Tings are kinda hard for me dis week, but–”

“Don’t worry yourself,” Tara reassured.

Throughout the meal, there was barely any talking at the table, just chewing, scooping, swallowing and loud gulps after drinking cherry Kool Aid that left a red stain on their lips. When they all finally collapsed into their chairs, Tara smirked. She looked at each drowsy face struggling to keep their eyes open. The loud smacking had turned into picking at whatever was left on the plate.

“Dis was good Tara. We need to do this again,” Paulette said in between chewing and licking the gravy off her thumb.

“Mi usually do this for me and Lani every Friday. Mek we do this together nuh?”

“You seem to live large.”

“I need something I can enjoy from time to time.”

“Mi’ wish mi’ could live like you. I wish I could spend a whole heap of money on oxtail whenever I want.” Paulette picked up another fork of rice, but looked through it as if entranced by her own bitterness. “It’s backbreaking work mi’ ah do every day. And at my age? At forty-six. I wish I was a young girl like you.”

Maybe it was because she hadn’t lived long enough to understand being hardened by disappointments that Tara chose to be quiet. She guessed that Paulette’s calloused hands carried a weight that she had never considered. Laugh lines with skin beginning to sag beneath them probably had a story to tell. When Paulette stretched and then slumped into the chair again, it was the first time Tara recognized her modesty. She wondered if Paulette ever wore jewellery or even makeup.

“Yuh think seh mi’ want to clean someone’s shit? To toss someone’s nasty body around and dress dem and feed dem like pickney? I do it because mi haffi do it. And mi’ just pick up a second job fi’ work at dat nursing home up there suh.”

“Yuh mean the one on Carpenter Avenue?”

“Yes, my girl,” Paulette nodded. “Yuh young girls don’t like to work. Just sitting around waiting fi’ man to rescue you.”

Tara didn’t mention being on her own in New York from the time she left home. There was no need to vent about a two-year relationship that ended and left her with a baby. Nothing could possibly measure up. All she could do was sit quietly in guilt.

“If yuh work on da weekends, who will watch the children?”

“Mi nuh figure dat part out yet,” Paulette said, lowering her head to pick at the last soggy pieces of cabbage.

“Let dem come spend da’ weekends with me until yuh get yourself together.”

“Yuh nuh have to trouble yourself.”

“No,” said Tara defiantly. “We women need to know how to come together and stand with one another.”

“You’re right,” Paulette said with a faint smile. “Mi’ glad mi’ have a friend like you.”

Each Saturday morning, Tara made her way to Paulette’s apartment to gather all the children. Not one for spontaneous activities, she made sure each weekend was different from the last. Trying hot chocolate in the city turned into a game of which store made it the sweetest with the most creative toppings. Just an hour into a visit at any museum brought on the whining and complaining until Tara led the children towards the exit. With the children reigniting her own childlike excitement, she bopped her head to the subway performers singing old-time Christmas carols and joined in the oohs and aahhs when admiring the Christmas tree at Rockefeller Center. Times Square was always the best high-energy treat that the children couldn’t get enough of, their eyes growing wide and alert as they looked up at the bright marquees. Even cheap plastic toy souvenirs at random gift shops which would’ve gotten a shrug from Lani, suddenly became the most magical toys to play with. One trip to the movie theatre, drinking large raspberry slushies and munching on a large extra buttery popcorn, was talked about for weeks. “Yuh should’ve seen it mommy,” Tara overheard when Paulette’s children ran into their mother’s arms after an exhausting day downtown.

ONE MONTH SLIPPED into the next and the haziness of late spring brought on a fit of restlessness. Tara tried to stifle her own need to explore without extra mouths and eyes that always needed something. Immediately, she felt guilty about her own freedom, and punished herself with reminders about women like Paulette – the ones who did not have the choice but to be chained to constant work just to get by.

“Yuh know Mommy’s birthday is next week,” Paulette’s son blurted out while Tara folded clothes in the laundromat one Sunday morning.

“We must do something special for her then because yuh mother works really hard to take care of you.”

Tara held the first image of Paulette in her mind. She never forgot the heavy laundry bag that Paulette carried on her back in the slushy snow that padded the street. The laundromat had fast become their special meetup spot, the place where they congregated regularly to share their lives. And each time, after the last folded shirt, Tara watched with uneasiness as Paulette threw the large laundry bag over her back and sauntered past the door to slowly disappear, until she was a faded blur.

On the day of Paulette’s birthday, Tara picked up a tray order of oxtail with rice and peas that came with a few fried dumplings and a litre bottle of ting. Only on special occasions did Tara set the tiny round table in the kitchen with gold placemats to match the gold silverware. At the centre of the table, she placed two white candles. Balloons from the dollar store drifted to the ceiling, the strings dangling in their faces as Tara and the children walked in and out of the kitchen.

Everything was in place, so there was nothing left to do but wait. Tara jumped into position when the buzzer blared from the intercom, her adrenaline pulsating. Shoving the children into the kitchen, she turned off the lights when she heard a knock at the door.

“Why is it so dark in here?” Paulette asked when Tara opened the door.

Tara guided Paulette’s hand inside until they were in the kitchen.

“Surprise!” Tara and the children shouted in unison when she switched the lights on.

“Oh my lord,” Paulette’s voice trailed off.

Tara saw her lips part open in disbelief. A few steps forward, and then Paulette swiveled around so quickly that Tara nearly fell from the tight embrace. “Thank you,” Paulette whispered into her ear as if saying it too loud would ruin such a moment.

“Dis isn’t everything,” Tara teased. Before Paulette could ask, Tara disappeared into the hallway. A few moments later, a door could be heard opening and shutting. Wheels ground against the wooden floor. Next thing Tara heard were belly-aching laughs, the kind where sound was suppressed by trickling tears, a pained laughter brought on by something so hilariously unexpected.

“A laundry cart!” Paulette squealed. This time it was Tara who was hit by the laughing bug.

“Mi’ tired of seeing yuh drag dat big bag into da laundromat. Mi cyan tek seeing it anymore.”

“All right, yuh nuh haffi worry yourself about it anymore.” Tara watched as Paulette grabbed the handle of the black laundry cart to test the wheels. She moved it back and forth a few times before setting it to the side.

Never had Tara seen her friend so relaxed. It was like bearing witness to a new, more confident woman – a woman newly christened with charm. Even the way she ate the oxtails was different. Instead of ripping the meat with her teeth, the bites were more delicate, perhaps a little too elegant.

Tara nibbled through the meal out of politeness and swatted Lani’s hand away when she reached for the bigger pieces of oxtail. At the end of the night, Paulette carried the tray of oxtail out of Tara’s apartment while her two children tugged at her coattails, fighting the sleep spreading over their eyes.

After she was hugged goodnight with all the praises of being one of God’s children to be protected, after she looked at her messy kitchen table that held all the scraps from one joyous night, Tara realized how happy she was for the first time in a long time.

THOUGH SHE NEVER TOLD Paulette, Tara looked forward to the Fridays they shared together. It was the single most important de-stressor in her life. To have one day where she didn’t have to overthink about what had to be done in preparation for the next day. With every step she took up the poorly lit stairs in Paulette’s red brick apartment building, she felt the comfort of having someone, which kept her calm and at ease.

She had the usual two orders of oxtail and rice and peas in one hand, and Lani in the other. When she approached 2F, the door was already cracked open. Loud percussions beat their way into Tara’s bones. Slowly pushing the door open as if anticipating an unexpected surprise, she saw Paulette shimmy her way into the kitchen. She followed cautiously, awestruck by Paulette’s extra bounce, the strange liveliness that had replaced her controlled reserve. With a loud thud, Tara dropped the bag on the kitchen table. Paulette jerked away from the window, where the natural yellow light sprayed every surface of the kitchen, leaving few spots of muted grey shadow. Tara was immediately frozen by surprise. Paulette was wearing a plum brown lipstick and a bit of blush. A lightly applied mascara drew attention to and brightened her large eyes in a way that Tara had never seen before. A bunch of gold bracelets on her left wrist jangled against her red, floor-length kaftan as she moved the chairs to the side to embrace Tara, who was still stuck with the same expression.

“Look at you Paulette!” Tara managed to say. “Mi’ nuh know today was a celebration.” Tara beamed proudly at Paulette’s new braids falling just past her shoulders.

“Mi’ just needed a change.” Not wasting any time, Paulette opened the containers and smiled warmly at what was now an expected pleasure.

As they now did intuitively, Tara, Paulette, and the children sat at the table and ate like a banded pack in the wild, feasting on their meal. Tara knew Paulette’s eating habits by now. She took the biggest oxtail first, cleaning the meat right off the bone, dipped the bone in brown gravy and sucked it until satisfied. Rice and peas were next. The mixed cabbage was always last, neglected to the point where it was only poked at.

“I was thinking about taking da’ kids to a candy store downtown tomorrow,” Tara offered in between the loud chewing. “Mi’ know they would love that!”

Tara crossed the fork and knife on her plate after she finished and couldn’t stomach anymore. She pushed the plate to the centre of the table and swung one arm off the back of her chair, perfectly contented.

“Yuh nuh need to take dem dis weekend. Me and da kids are going to be in Jersey.”

“New Jersey?” Tara’s head perked slightly in Paulette’s direction. “Mi’ never know yuh had family in Jersey.”

“I don’t,” Paulette said. “Mi’ just put a down payment on a house in Jersey and mi’ meeting someone tomorrow to help clean it out.”

Tara moved the arm hanging lazily behind the chair like it was brought back to life. She leaned into the left side of the chair, her weight supported by the armrest, to hold all pressure in one place. She stared at Paulette as if she was seeing her for the first time. Focused and strained, she looked at her own empty plate, at the children munching away without a care, at the last bits of rice and soggy cabbage left in the container, and then back at Paulette’s colourless lips smudged with brown gravy.

“How long were yuh planning to buy a house?” asked Tara, trying not to sound accusatory.

“A few years now.”

Tara stared intensely as Paulette licked the brown gravy off her lips and daintily patted the corners of her mouth with a napkin.

“Really,” Tara willed herself to say as if words were lodged in her throat. Through trembling lips, she began to open her mouth again to ask a question, but what came to mind seemed too foolish and quarrelsome to ask. Defeated, she folded her arms and looked down at her lap. “That is nice Paulette.”

She listened while Paulette talked about her plans for the big move at the end of the month. From every piece of furniture kept in storage that would have to be delicately unwrapped, to her ex who was flying in to help refurbish the floorboards, Tara felt assaulted by each detail.

“Yes my dear, nuff time me spent in dis place here suh.”

The only thing that pulled her out of

the inner whirlwind of questions which had made her go deaf to anything said, was the sound of a plate being scraped. Every grain of rice and each soggy piece of cabbage that Paulette emptied into the trashcan held Tara’s attention.

For weeks after Paulette moved, Tara called regularly with a determined effort to be pleasant. She heard about the big space, where the children could run around in an empty driveway, where no cars blocked or double parked. How renovating the kitchen would be pricey but doable with money from the second job to cover any extra costs. How safe the neighbourhood was, how she was finally free from hearing couples argue about nothing, free from foul smells triggering migraines. During each phone call, Tara heard about every convenience found in this suburban haven until she was rushed off the phone for someone that stopped by. Eventually, a few calls every week became one call a month until, when she did try to call, instead of the usual three rings and answer, her calls were sent directly to voicemail.

Morgan Reid holds a Master’s in Writing degree from Johns Hopkins University. Her work has appeared in Otherwise Magazine, and her op-eds and book reviews have been featured in The Baltimore Times. She has taught First-Year Writing at the New Jersey Institute of Technology and currently

works as a Technical Editor. She lives in Maryland and is working on her first novel. Instagram: @themorganreid